How the ball point pen killed an industry

How the ball point pen killed an industry (Or how booms usually end in a bust)

In the later part of the 19th Century, prospectors on Tasmania’s rugged West Coast kept finding a white, hard metal in their gold panning dish.

That metal was osmiridium – a natural alloy of the elements osmium and iridium – but to the prospectors, it was simply a nuisance. Not only was it worthless, but they were penalised if the gold they sold contained any traces of osmiridium.

As a result, the small, dense pieces of white metal were carefully removed from the recovered gold, and thrown away.

Forty years later, Tasmania was the world’s largest producer of premium osmiridium, commanding prices (in today’s dollars) of over $5,000 per ounce.

Making a better pen

Around the time Tassie prospectors were throwing away their osmiridium haul, investors in Europe were trying to perfect the fountain pen.

For centuries, writers had used a goose or swan quill dipped in ink. A pen containing a reservoir of ink was an obvious improvement. But the early fountain pens leaked, were messy to fill, and unreliable.

Initially, steel nibs were used although they corroded rapidly and needed regular replacement. And then, somebody came across a solution – a gold nib, tipped with the densest alloy on the planet – osmiridium.

Immediately, pen companies began scouring the globe searching for a reliable osmiridium supply. Although the metal was found in a number of countries, the granular structure was unsuitable for pen manufacture. In only one place did the metal occur in the right size and shape for use in fountain pens – Tasmania’s West Coast.

The new mining boom

Mining booms were common in early Tasmania, and the remote parts of the state are littered with the remnants of abandoned mining towns.

By the beginning of the 20th Century, many of the early mining claims were no longer productive, and most of the larger deposits had been discovered. Thousands of prospectors were out of work.

Until the osmiridium buyers came calling.

When commercial quantities of osmiridium were discovered at Bald Hill, prospectors rushed to stake their claim. As the price of the metal kept rising new fields were sought, and eventually, the world’s largest deposit of osmiridium was found in the remote Adams Valley in Tasmania’s South West.

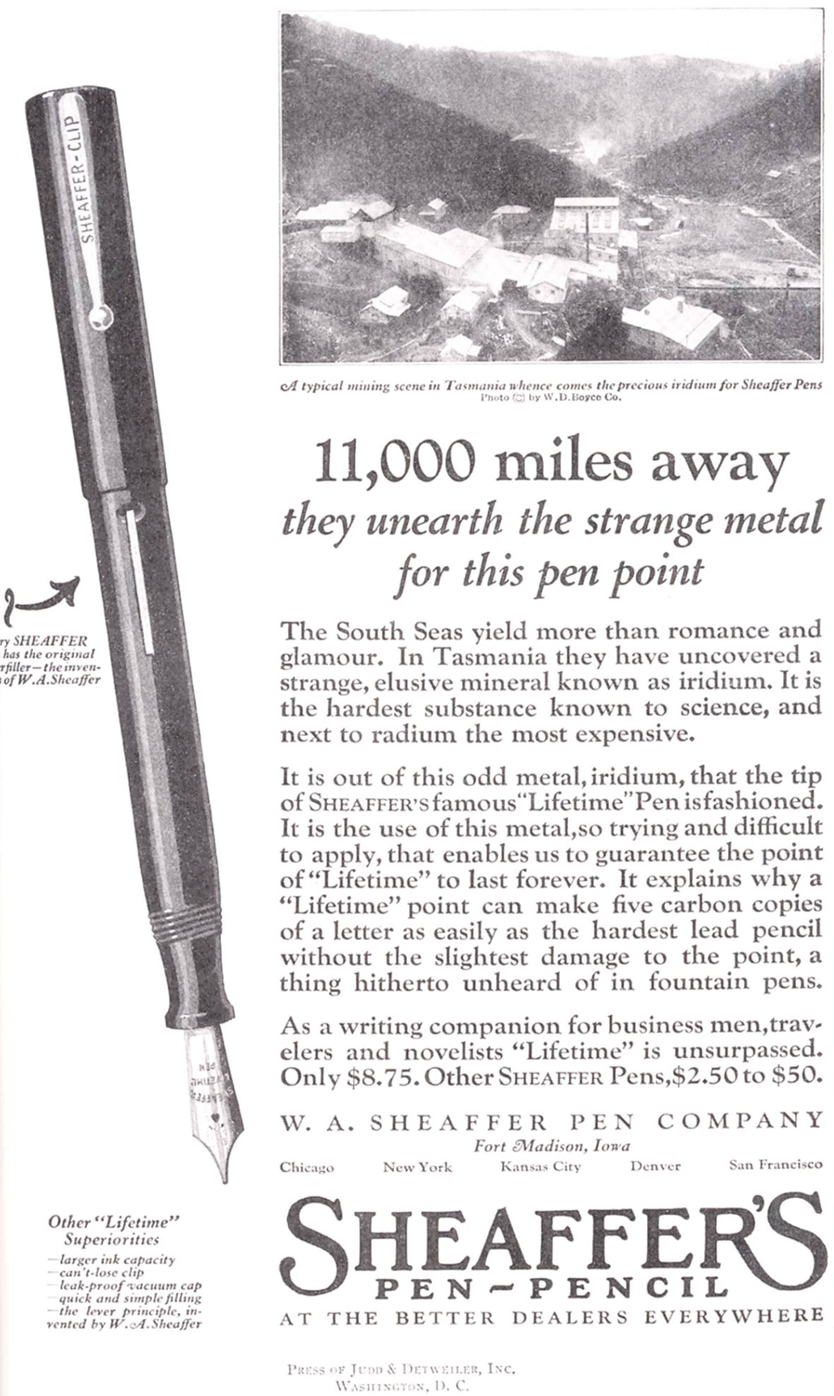

Adamsfield, as the new settlement became known, was quickly home to 2,000 workers and their families. Many lived in tents, in some cases for years on end, despite the often atrocious weather. With osmiridium trading at seven times the price of gold, to many, those hardships were bearable.

By 1926, the importance of the industry to Tasmania’s economy was such that the government considered bringing the mining, marketing and selling of osmiridium under state ownership.

But all booms eventually end, and the Great Depression, followed by WW2 forced all manufacturers to cut costs. Pens producers were no exception, and most of the larger companies replaced osmiridium pen tips with tin.

The final nail in the coffin

Mining at Adamsfield continued through the war years, with miners optimistic that demand for the metal would return once austerity measures were lifted.

But the final blow came in 1945, when the ball point pen was released to the mass market. Ball point pens were cleaner and more reliable than fountain pens, and available at a fraction of the cost. Demand for osmiridium vanished virtually overnight.

A few hardly souls continued mining at Adamsfield, but the market never recovered, and the last resident left in 1960.

Today, only relics remain. Fires have destroyed most of the buildings, and the bush is gradually reclaiming the evidence that Adamsfield was once a bustling township.

Osmiridium today

Fountain pens are now very much a niche product, with most manufacturers using modern alloys for the nib.

But other uses have been found for osmiridium, including surgical instruments, electrical contacts and other technical applications where an extremely hard-wearing metal is required.

The metal is no longer multiple times more valuable than gold, instead trading at around US$400 per ounce.