Are Blue Chips Still Blue?

Tom Elisson

Thu 25 May 2023 7 minutes“The art of successful investment lies first in the choice of those industries that are most likely to grow in the future and then in identifying the most promising companies in these industries.” - Benjamin Graham

32 years ago, everybody who held a Commonwealth Bank account received a hefty document in the mail.

It was an invitation to become a shareholder in the bank, which until then had been government-owned. The minimum investment was 400 shares at a price of $5.40 – a total of $2,160.

The canny people who wrote out a cheque for $2,160 and put their share certificate in the bottom drawer are today sitting on a holding worth around $52,500. That’s a 1,700 per cent return.

But there’s more. This financial year, CBA has paid dividends of $4.20 per share – nearly as much as the original cost of the shares. Since listing on the ASX in 1991, the company has paid the staggering total of $76.42 per share in dividends. And every dividend has been fully franked.

To many, that track record makes CBA the bluest of Blue Chips.

Trust us. We’re from the government.

A couple of years later, the government floated the old Commonwealth Serum Laboratories on the ASX. A $1,000 investment in CSL Limited then would today be worth just shy of $400,000.

CSL is now one of the world’s leading biotechnology companies. It’s as blue as Blue Chips can get.

CBA and CSL are Australia’s second and third biggest listed companies respectively. Only BHP (yes, another Blue Chip) is larger.

But the shift from government to private ownership isn’t automatically a recipe for wealth. In 1997, investors paid $3.30 per share when Telstra went on the market. Today, those shares are trading at around $4.35.

What’s a Blue Chip, anyway?

There’s no real definition. A common description is “a well-known, profitable company with a good reputation.”

Others suggest a history of paying steady dividends gives a company Blue Chip status. Or simply being in a list of the ten or twenty biggest companies in a market.

There are a lot of grey areas in those definitions of blue. And plenty of problems with each.

Well-known companies

Nearly all companies that often carry the Blue Chip tag are household names in Australia. That includes the major banks, supermarkets like Coles, and miners BHP and RIO Tinto.

Trouble is, although most Blue Chips are household names, not all household names are Blue Chips…

Possibly due to sheer force of advertising, Harvey Norman is a brand most Australians would be aware of. Yet it’s not even in the list of Australia’s 100 largest companies.

AMP, once a goliath of the insurance industry, is now a minor player. It’s reputation still clouded after years of negative publicity, AMP shares have lost more than 90 per cent of their value since listing decades ago.

This creates a risk for investors who don’t have a lot of experience. Faced with a choice, most people would instinctively choose Harvey Norman ahead of, say, Allkem Limited thinking that a well-known business is likely to be a safer bet. As the share price history of AMP shows, that’s not a reliable way to pick stocks.

Strength in size

The 1980s was a glorious decade for investors in the sharemarket; until October 1987 at least.

It was the time of big egos, big takeovers and even bigger debt. Between them, business leaders John Elliott, Robert Holmes à Court, John Spalvins, Alan Bond and Ron Brierley owned or controlled nearly all of Australia’s biggest businesses.

The giants of the ASX included Elders, Industrial Equity Limited, Adsteam, Tooth & Co, David Jones and Woolworths.

All are now gone – either bankrupt, or under new or radically changed ownership. An investor with a portfolio of Blue Chip shares in the mid 1980s would have been left with a draw full of worthless share certificates a decade later.

Which suggests ‘bigger is better’ shouldn’t necessarily be the name of the game when it comes to investing in shares.

Australia. A Blue Chip backwater?

The ten largest listed companies in Australia have a lot in common. For a start, half of them are banks – the oldest being Westpac, founded (in a very different form) in 1817. As well as those banks, there are three mining companies, a retailer (Wesfarmers, owner of Woolworths) and CSL Limited.

That’s a lot of history, but not necessarily a lot of innovation.

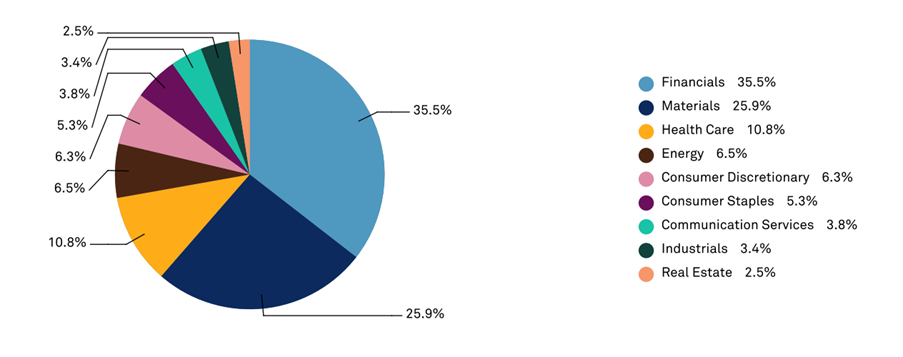

Here’s a snapshot of the twenty biggest companies on the ASX. Banks and mining companies make up nearly two thirds of the total value.

More than 2,400 individual companies are listed on the ASX. Yet the direction of the market overall is dominated by that handful of banks and miners.

Let’s take a look at the United States, where a bank doesn’t even make the top ten.

Seven of the top ten are technology stocks in various guises. We’re no longer talking about dotcom penny dreadfuls; we’re talking the biggest and most profitable companies in history. Apple. Microsoft. Amazon.

Most of them are young companies. Two of them (Tesla and Facebook-owner Meta) didn’t even exist during the dotcom boom.

Apple is a relative youngster, first listing on a stock exchange in 1980, Today, the company is worth more than $4 trillion – nearly twice the value of every stock on the ASX combined.

But don’t Blue Chips provide better returns?

Not necessarily. Yes, some stocks like Commonwealth Bank and CSL have provide stellar returns for shareholders. Others? Not so much, particularly in recent years.

The share prices of half Australia’s top ten (ANZ, Westpac, NAB, Woodside and Telstra) are lower than they were a decade ago. Yes, there have been regular dividend payments, but for investors hoping for some capital appreciation, it hasn’t been a great outcome.

Even taking dividends into account, annualised returns for those stocks has only ranged from 2.7 per cent to 5.2 per cent over the last ten years.

That can be a problem, particularly for investors who’ve focused on Blue Chips expecting strong returns.

The truth is, Blue Chips (in Australia at least) often provide lower returns than small or mid-sized companies because they tend to be mature businesses with limited growth prospects.

A safety blanket

Type “should I invest in Blue Chips?” into your search engine, and you’ll be rewarded with all sorts of positive messages.

Blue Chip stocks are smart choices, one article suggests. Another says Blue Chips offer safety and stability, together with a share price that will consistently grow over time. Another post even implies Blue Chips are safe investments.

All of this should be treated with caution.

The term ‘Blue Chip’ is just a label. It’s not a guarantee of performance, nor does it make a stock superior to the countless other opportunities in investment land.

Yes, it’s comforting to be told that your investment choices are good ones, and picking Blue Chip companies comes with that implied endorsement.

But as with any investment, you need to focus on the quality of the product, not just accept what’s written on the label.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Tom Ellison. It is for educational purposes only. Prices and valuations were current as at 19 May 2023. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.