Risky Business – the 2023 Federal Budget

Economic forecasts are rarely accurate. Any Federal Treasurer will tell you that.

Just four years ago, then-Treasurer Josh Frydenberg forecast a surplus of $7.1 billion for 2019/20. After paying for the unexpected impacts of bushfires and the Covid crisis, that predicted surplus turned into an $85 billion deficit.

In his first Budget late last year, incoming Treasurer Jim Chalmers announced a forecast deficit of $36.9 billion. Now, just seven months later, that deficit has vanished. Instead, Australia looks likely to record its first fiscal surplus in 15 years.

With all the resources of the public service available to the Treasurer, you might wonder – how could those forecasts have been so wrong?

In the first example, Frydenberg’s numbers were scuttled by Covid. In the second, the incoming Labor Government’s Budget was rescued by rampant inflation, which drove tax receipts higher. Not to mention record tax revenues from booming commodity prices.

It wasn’t possible to predict the impact of the Coronavirus crisis. It appears nobody predicted the rapid resurgence of inflation either.

But predictions and assumptions are important. Actually, they are critical to the Budget process. While the short-term media attention might be on Budget ‘winners and losers’, it’s also worth looking at how the Government plans to pay for its proposed spending into the future.

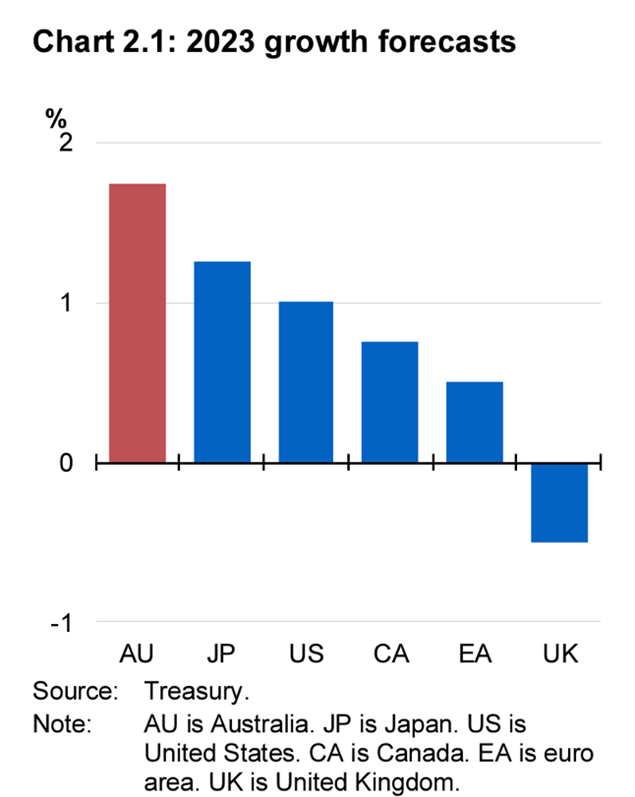

Economic growth forecasts

If we believe the Budget papers, we’ve managed to sidestep a recession. In nominal terms (not taking inflation into account), Australia’s economy is powering along at a rate of over 10 per cent. Net of inflation, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth is still a reasonable 3.25 per cent.

But darker times lie ahead. Thanks largely to much higher interest rates, that growth is expected to fall sharply – below 2 per cent for the 2023 calendar year, and down to 1.5 per cent in the 2023/24 year.

That still puts us well ahead of the major global economies. But as mentioned earlier, these are forecasts, not facts.

A sharper than expected slowdown could make that 1.5 per cent forecast optimistic – and that’s just one of the risks outlined in the Budget documents:

“The outlook for growth in advanced economies remains highly uncertain with risks firmly weighted to the downside.”

A key risk is instability in the banking sector. Financial modelling gives us an idea of what might happen if a number of small financial institutions in the global banking sector fail.

Although Australia would be relatively isolated, there are still flow-on effects, like falling asset prices, higher investor risk aversion and a significant jump in unemployment. Growth would fall by 0.5 per cent.

Obviously, a more severe shock akin to the GFC would have far greater consequences.

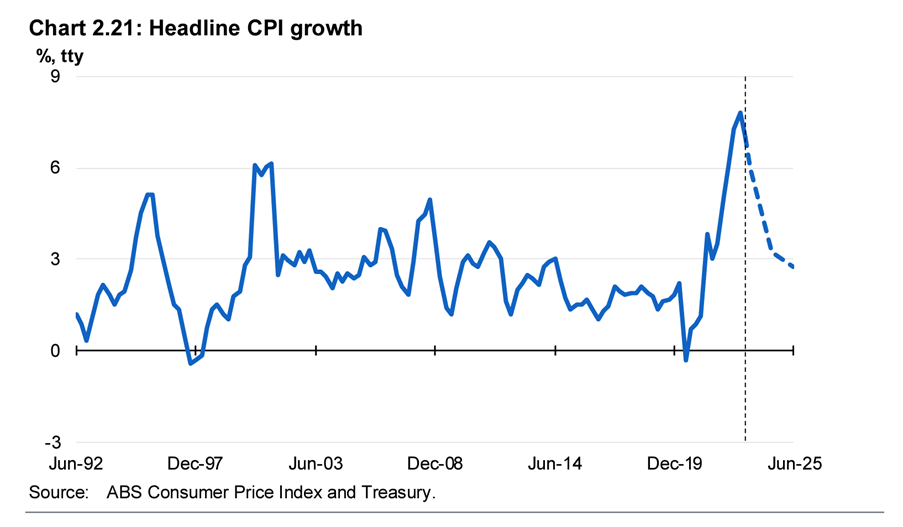

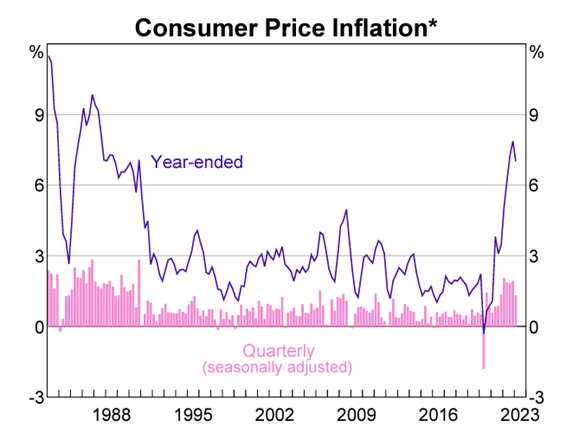

Inflation is falling. But how quickly?

If Treasury is correct, the Reserve Bank has done its job. Through a rapid-fire string of rate rises, taking the official cash rate from 0.1 per cent to 3.85 per cent, inflation is now under control. Or is it?

Inflation, the Government says, peaked late last year, and is now on the way down.

Annualised inflation was 7.8 per cent in the December quarter of 2022 and 7.0 per cent in the first quarter of 2023.

The Budget papers extrapolate that decline to come up with annual inflation of below 3.0 per cent within two years. In the shorter term, the Budget suggests inflation could drop as low as 3.25 per cent in the June quarter next year.

Given the Reserve Bank’s target range for inflation is between 2.0 per cent and 3.0 per cent, those forecasts would suggest interest rates should start falling within a year, providing welcome relief to borrowers.

But history suggests inflation can be hard to tame. Before the Reserve Bank was given responsibility for using monetary policy as a tool in the early 1990s, periods of inflation typically ended in a recession.

Since that time, inflation has been benign, only emerging as a problem early last year. The Bank has copped a lot of criticism for the severity of recent rate rises, but if inflation has been tamed, those unpopular rate rises would seem warranted.

If the Bank’s actions were effective, we’ll find out soon. The Budget papers suggest inflation will fall to 6.0 per cent in the June quarter. In late July we’ll find out whether those forecasts are accurate, or whether inflation is remaining stubbornly high.

The elephant in the budget room

Many of the newspaper headlines highlight the Budget surplus for 2022/23. That’s not surprising, because surpluses don’t come along that often.

And if Treasury’s forward estimates are accurate, it could be a long time before we see another.

What we’ll also be waiting a long time for is a reduction in government debt. Debt doesn’t get much focus in the Budget documents, but it hasn’t gone away. Actually, it’s still growing.

Back in 2019 before the Covid Crisis, Australia’s government debt stood at around $539 billion. Today, it’s $887 billion – and growing. According to the Treasurer, gross debt will peak at $1.067 trillion in 2026, provided there aren’t any economic stumbles along the way.

Governments tend to talk about debt in terms of percentages of GDP, possibly because 36 per cent of GDP doesn’t sound as intimidating as $1,067,000,000,000. Or framed slightly differently, about $36,000 for every Australian.

That trillion-dollar debt doesn’t disappear in 2026, either. It will still be there a decade later, costing around 1.3 per cent of GDP to service each year.

The glass half-full Budget?

Predictably, when a Treasurer tackles the middle ground, nobody is particularly happy and with Chalmers’ Budget, it’s no exception. Already, various lobby groups are asking why they missed out. Some see higher income support payments as blessed relief from cost of living pressures, while others see it as wasteful spending.

But the Treasurer has delivered what nobody else has managed to do since before the GFC – a surplus, while still committing funds to soften the social impact of rising inflation, including spiralling housing and general living costs.

Yes, it’s a glass half-full Budget because some of the underlying assumptions could be optimistic. We’ll find out in coming years.

In the meantime, Jim Chalmers has thrown down a challenge to any argument that the former Government was better able to manage Australia’s economy.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Tom Ellison. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.

Image References: 1.Budget Paper #1, p45 2.Budget Paper #, p66 3.https://www.rba.gov.au/chart-pack/aus-inflation.html