The Dalio dilemma

Simon Turner

Thu 18 Jul 2024 6 minutesLearning from successful professional fund managers is often a shortcut to better investment results. It’s equally informative when there’s a noteworthy shift that brings a previously successful investment strategy into question. Enter the Dalio dilemma.

Ray Dalio made famous an investment strategy called risk parity which was created as an all-weather strategy with the objective of making money in a diverse range of market environments.

But the strategy’s significant underperformance of the US stock market, particularly the Magnificent 7, has inspired some investors to run for the exits in recent years. This not uncommon tale raises important questions about investment timeframes, when to stick with your fund manager, and when to cut your losses.

Risk parity introduced

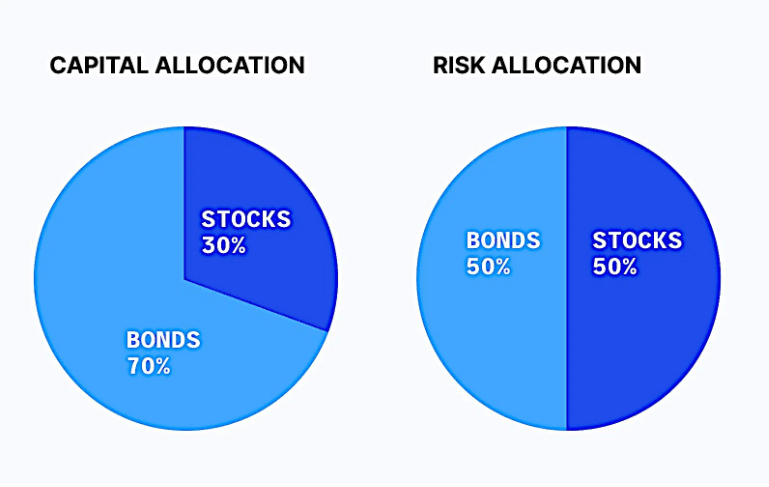

Risk parity investing is a strategy which allocates capital based on asset class risk, usually defined by volatility. It aims to deliver higher risk-adjusted returns and resilience during market downturns than traditional portfolios by setting the asset class weightings so that the contribution to portfolio risk from each asset class is roughly equal.

Risk parity portfolios are intended to better weather market volatility than a typical 60/40 portfolio, which is highly influenced by the performance of equities due to the 60% weighting. In contrast, a typical risk parity portfolio may be 70% invested in bonds and 30% invested in stocks in recognition of the higher risk profile of stocks versus bonds (at least, looking backwards).

Ray Dalio was the poster-boy for risk parity investing since he pioneered the approach at Bridgewater Associates in the mid 90s until he gave up the reins almost two years ago.

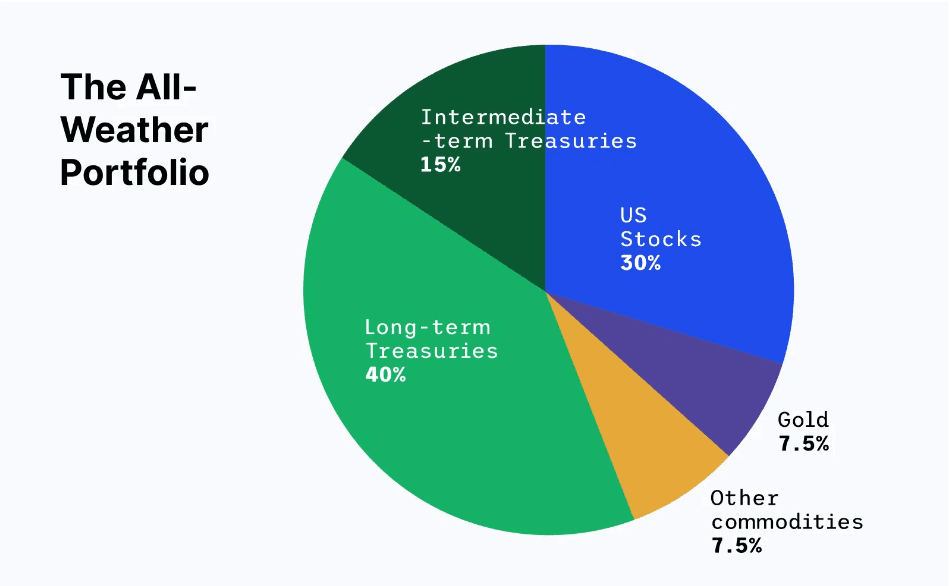

Here’s a basic version of the All Weather Portfolio he made famous.

As you’d expect from a portfolio built upon risk parity by asset class, this strategy has the highest weighting in the asset class with the lowest volatility which is bonds (in theory), followed by stocks, and the higher volatility commodities.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

Enter the Dalio dilemma

Investors love their fund managers when they’re winning.

But when a strategy is out of favour, it’s often an entirely different story.

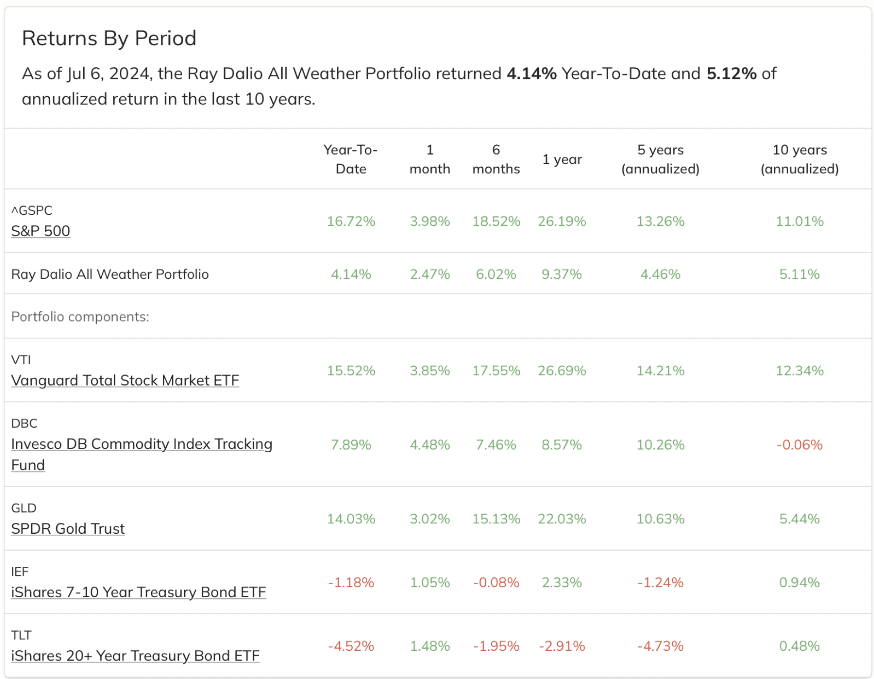

The Dalio dilemma is a cautionary tale on that front. Bridgewater Associates’ risk parity funds have been underperforming in recent years due largely to the relative weakness in the global bond market. As shown below, the All Weather Portfolio has underperformed the S&P 500 by 9% p.a. over the past five years.

Of course, this recent underperformance shouldn’t be a shock to investors given what’s been happening in bond markets. The iShares 7-10 Year and 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETFs are both in negative territory over the past five years, creating a strong headwind for risk parity strategies with large bond weightings.

As a result of this underperformance, Bridgewater Associates has suffered fund outflows for some time now.

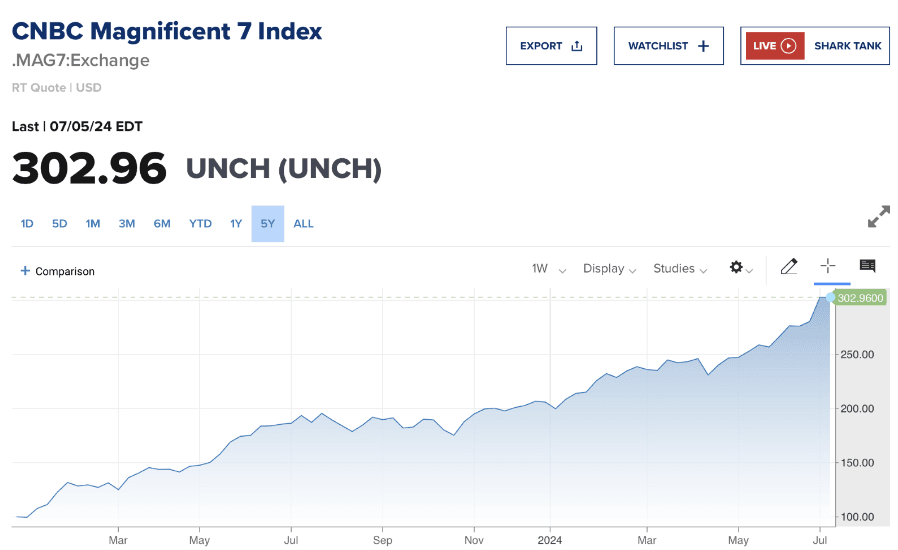

Beyond bond market weakness, here’s the Dalio dilemma arguably summarised in one chart…

The Magnificent 7 stocks have outperformed risk parity and other more conservative strategies so dramatically over the past five years that some investors have become frustrated. Rather than FOMO, it’s a case of AAMO (Annoyance At Missing Out).

Of course, there’s more at play here, including potential cultural issues at Bridgewater as well as Ray Dalio’s recent retirement, but the broader theme is noteworthy: investors have been selling funds and assets which were purchased for the purpose of navigating challenging market conditions for the sole reason market conditions haven’t been challenging for some time now.

But what came first … the chicken or the egg?

Broader questions raised & quotes which may answer them

The Dalio dilemma raises a number of important questions for fund investors…

Have investors become too focused on short term returns?

Seth Klarman would probably argue they have: ‘The single greatest edge an investor can have is a long-term orientation.’

Translation: Investors are likely to make more money if they start thinking genuinely long term about fund investing. That means not judging funds on their short term returns when market conditions haven’t been in their favour.

Should investors give up on a conservative strategy created to weather all seasons just because it is underperforming the equity market?

One of Mr Buffet’s most-quoted quotes suggests not: ‘Be fearful when others are greedy. Be greedy when others are fearful.’

Translation: Now’s probably not the right time to be selling out-of-favour conservative strategies for the sole reason that equity markets have gone up a lot. In fact, it’s generally the opposite: the more expensive stocks are, the more vulnerable they are to a selloff—and the more appropriate conservative strategies are.

Should investors look backward or forward when deciding how to allocate their capital?

Mr Buffet perfectly describes the problem with looking backwards: ‘Most people get interested in stocks when everyone else is. The time to get invested is when no one else is. You can’t buy what is popular and do well.’

Translation: Now’s maybe not the ideal time to be going all-in on the strategies which are crowded and overbought such as the Magnificent 7 stocks at the expense of your more conservative, out-of-favour funds and assets.

In the past, the winning and losing asset classes have tended to be different each year which meant it was important to have an appropriate level of asset class diversification. But that’s not been the case for a few years now as the Magnificent 7 stocks have had their historic run. Does that mean global markets have fundamentally changed since the pandemic?

Sir John Templeton famously warned against assuming the world is different from the past: ‘The four most dangerous words in investing are: “this time it’s different.”’

Translation: It’s unlikely to be different this time which means next year’s winners probably won’t be the same as this year’s. Hence, it’s probably prudent to assume a change in market leadership in the coming months and years. In other words, don’t put all your eggs in the Magnificent 7 basket.

Subscribe to InvestmentMarkets for weekly investment insights and opportunities and get content like this straight into your inbox.

The merry go round will keep going until it doesn’t

The Dalio dilemma raises broader questions about recent asset allocation trends in a global market that’s becoming more myopic by the month. With more investors looking backward for a guide of what’s to come, the Magnificent 7 continue their relentless rise at the expense of all other strategies and asset classes.

Now may be the right time to ask: what if it’s not different this time? Being exposed to the more conservative funds which have underperformed the Magnificent 7, such as risk parity, could well be prudent ahead of the arrival of the market’s next season, whenever it chooses to arrive.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.