‘Britain’s Warren Buffet’ & the Discipline of Being Early

Simon Turner

Mon 19 Jan 2026 7 minutesAnthony Bolton, often described as ‘Britain’s Warren Buffett’, remains one of the few modern investing masters whose reputation rests not on a single cycle or style tailwind, but on a long, verifiable record of compounding through multiple market environments. His edge came from a disciplined process applied consistently over nearly three decades, combined with a rare willingness to sit with discomfort. There’s plenty to learn from this investment legend…

Who is Anthony Bolton?

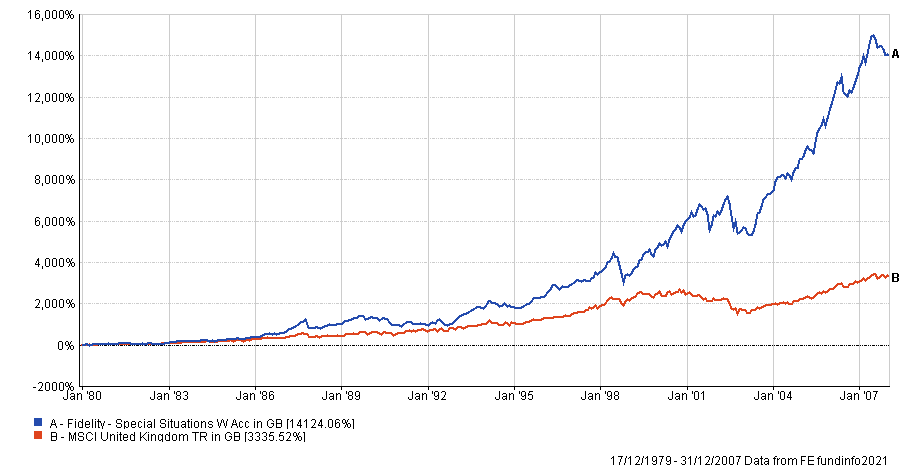

Bolton managed Fidelity’s Special Situations Fund from its launch in December 1979 through to the end of 2007. Over those 28 years, the fund delivered a return of 19.5% p.a., compared with 13.5% p.a. for the FTSE All-Share. That 6% p.a. of outperformance, sustained across recessions, inflation shocks, market bubbles, and market crashes, places his track record among the strongest in modern active management.

The power of compounding turned Bolton’s edge into something profound. £1,000 invested in his fund at launch grew to £147,000 by the end of 2007, almost five times what it would have been worth if invested in the broader market.

Bolton’s track record serves as irrefutable evidence that long-term investment outcomes are determined by process and persistence, rather than episodic brilliance.

A Unique Type of Contrarian

In his book Investing Against the Tide Bolton himself was up-front about what his process required of him:

‘When you have a fish on the line you have to know when to pull them in and when to give them more line. In the same way, knowing when to be aggressive in buying or selling and when to stand back and let the market come to you is part of the skill.’

Although Bolton was often labelled a contrarian, his approach was not about reflexively opposing consensus. It was about identifying valuation anomalies, understanding why the market had mispriced them, and waiting for reality to assert itself.

Crucially, he understood that markets discount the future, not the present:

‘The stock market is an excellent discounter of the future – never underestimate this. It moves on what investors in aggregate expect to happen in the real world in six to twelve months’ time.’

This explains why Bolton’s strategy often looked wrong before it looked right. A contrarian strategy, by definition, is misaligned with prevailing narratives. As a result, it often underperforms when momentum dominates and excels when expectations eventually mean-revert.

Bolton accepted this pain profile as intrinsic to his strategy rather than as evidence of failure. And he was able to sit with that high level of discomfort with remarkable fortitude, which is arguably one of the rarest but most essential attributes of a master investor.

This is one of his most valuable lessons for investors: if you can’t tolerate a strategy’s periods of underperformance, you shouldn’t own it.

His focus on ‘special situations’ reinforced this mind-set. He wasn’t buying cheap stocks without catalysts, but companies undergoing fundamental changes such as restructurings, balance-sheet repairs, management transitions, spin-offs, cyclical recoveries, or reputational overhangs.

So he wasn’t focused on valuation alone, but a credible catalyst that could close the gap between price and intrinsic value. In fact, Bolton repeatedly warned that buying something merely because it looks cheap isn’t fundamental investing. He saw it as speculation without a timetable.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

The Value of Understanding Market Psychology

Equally important to Bolton’s success was his understanding of market psychology.

In Investing Against the Tide, Bolton devotes significant attention to behavioural errors, most of which remain as relevant today as when he wrote them. His observations read less like theory and more like hard-earned field notes. For example:

‘We need to keep an open mind. Once we buy shares, we become less open to the idea that our decision to buy was wrong. We close our mind to evidence that doesn’t confirm our initial thesis.’

This awareness of confirmation bias is core to effective risk management. The danger is not ignorance, but selective attention.

Bolton also challenged the authority of consensus:

‘Many supposed experts are not. Many experts never change their view. They remain with a permanently positive or negative view of the world or companies knowing they will be right part of the time.’

The takeaway is useful: confidence and frequency don’t equal insight, and rigidity is often mistaken for conviction.

Being aware of overconfidence risk was another Bolton specialty:

‘We all think we are better at investment than we are.’

Further to this point, a good run, he believed, was more dangerous to discipline than a bad one.

Bolton are aware investors are also prone to asymmetry in decision-making:

‘We are too conservative when we take gains and too relaxed in running losses.’

This is a notorious behavioural pattern that erodes many investors’ long-term returns. Running your winners and cutting your losers is psychologically challenging for most investors.

Bolton was also acutely aware of how recent experience distorts probability assessment:

‘Investors underestimate the likelihood of rare events happening when they haven’t happened recently, while they overestimate them when they have.’

This is recency bias in all its glory. It continues to drive cycles of complacency and panic today.

Tying Bolton’s awareness and over-riding philosophy together was a simple but confronting test he often asked himself about his portfolio: if he didn’t own it today, would he buy it again at this price? This question strips away sunk-cost fallacy and forces investors to re-underwrite their positions in the present tense.

A Memorable Wobble Along the Way

Bolton’s career was so instructive not because it was one hundred per cent flawless, but because its most visible failure was so public.

After retiring from running Fidelity’s Special Situations Fund, he returned to manage Fidelity’s China Special Situations Fund, launched in April 2010 with an IPO that raised £460 million.

Early performance was encouraging, with a 7.7% return between April and September 2010, well ahead of the 1.4% generated by the MSCI China Index over the same period.

However, just when investors were expecting more of the same, a sharp reversal followed. The fund’s share price fell over 40% to 70p.

Bolton’s own post-mortem was truthful and unambiguous: he’d underestimated corporate governance risk in China.

This wasn’t a minor oversight. Governance resides at the very heart of what value means in a market with different disclosure standards, incentive structures, and shareholder protections.

Bolton’s lesson was both humbling and enduring.

The takeaway for investors is that valuation ratios aren’t universal truths. They’re claims on future cash flows embedded within legal, cultural, and governance frameworks. When those frameworks differ materially, the margin of safety must expand accordingly. Bolton’s Chinese experience stands as a reminder that skill is contextual, and not necessarily portable by default.

Subscribe to InvestmentMarkets for weekly investment insights and opportunities and get content like this straight into your inbox.

Learn from a Master

So what should investors take from Bolton remarkable career today?

1. Sustained outperformance is the result of a repeatable process, rather than episodic insights. A 6% p.a. annual edge compounded over decades dwarfs short-term brilliance.

2. Contrarian investing requires a non-consensual view plus a catalyst, not simply disagreement with consensus. You must be right for a reason.

3. Patience is not passive. It’s earned through research, balance-sheet analysis, and an understanding of the potential downsides. The work precedes the waiting.

4. Emotional biases affecting our confidence, loss aversion, recency preference, and confirmation are structural and universal. True edge comes from recognising them within yourself and exploiting them in the market at large.

6. Humility is essential. Bolton’s willingness to reflect openly on his failures is part of what makes his track record so human rather than mythological. Markets change, regimes shift, and no process is universally applicable.

Earning the Right to Wait for It

If there’s a single lesson worth taking from this investment legend, it’s this: Anthony Bolton teaches us that the hardest part of investing isn’t finding value, but earning the right to wait for it without losing discipline, humility, or self-awareness along the way.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.