The misunderstood downsides of long-term investing

Ankita Rai

Thu 29 Aug 2024 6 minutesWhile long-term investing is often touted as the key to success in the stock market, there’s a body of evidence that challenges the idea.

Even Warren Buffett, who championed the 'forever' investing style, has occasionally betrayed his advice. Research shows that out of 230 stocks held by Berkshire Hathaway between 1980 and 2006, 60% were owned for less than a year. So even staunch long-term advocates adjust their strategies based on market conditions.

And rightly so. Predicting the distant future is tough. Industries can change, sectors can shift, companies get acquired or fail, making long-term bets far from uncertain.

The buy-and-hold strategy has proven especially challenging during periods of heightened volatility such as during the 2008 financial crisis and in 2020 when whipsawing markets saw investors with low-turnover strategies struggling, as they were unable to swiftly adjust their exposures.

Accurately predicting investment outcomes can be a challenge in any investment strategy, but the consequences of getting it wrong become more pronounced over longer investment horizons. So the buy-and-hold approach may not always be the most reliable strategy over the long haul.

The decline of long-term investing

Financial history is littered with instances where supposedly durable investment features have been turned on their heads.

For instance, in the 1980s, Japan led the global economy, the internet was still emerging, and Australian materials and gold stocks were highly prized. Today, the investment landscape has shifted dramatically, with technology leading the way.

Similarly, during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the S&P/ASX 200 Index fell nearly 50% from its peak. Investors who adhered rigidly to a long-term strategy saw their portfolios halve in value, with a full recovery taking over six years.

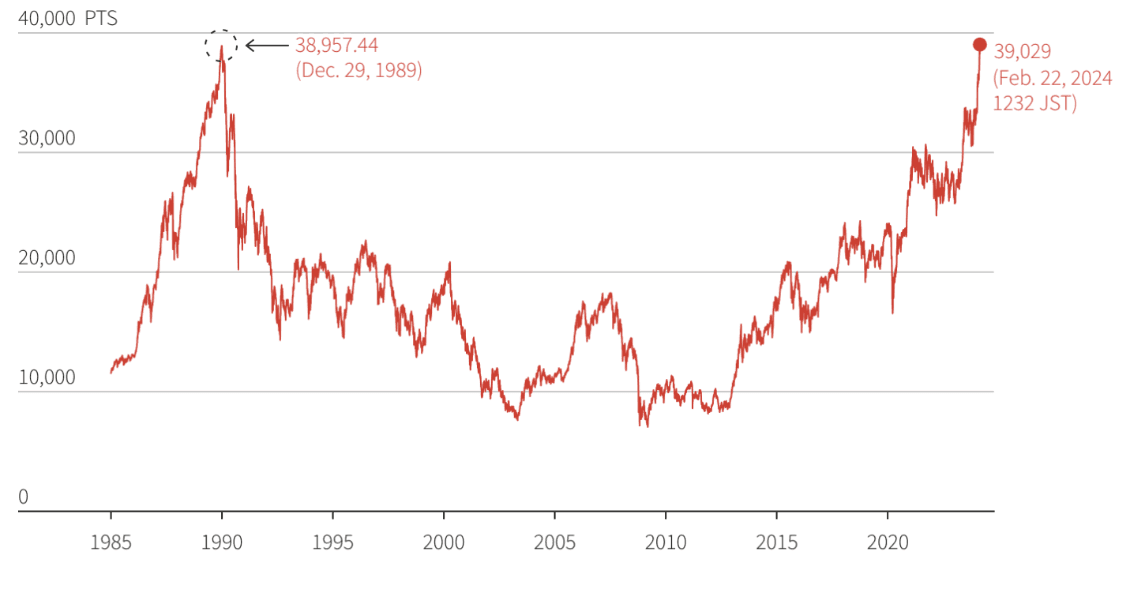

In Japan, the Nikkei 225 took 30 years to climb back to the peak of 39,000 it recorded in December 1989, showing how elusive long-term recovery can be. Investors who expected a quick rebound faced decades without seeing their investments returning to peak valuations.

This highlights how the foundations of long-term investments can shift, making them far from foolproof, especially in markets facing persistent economic issues.

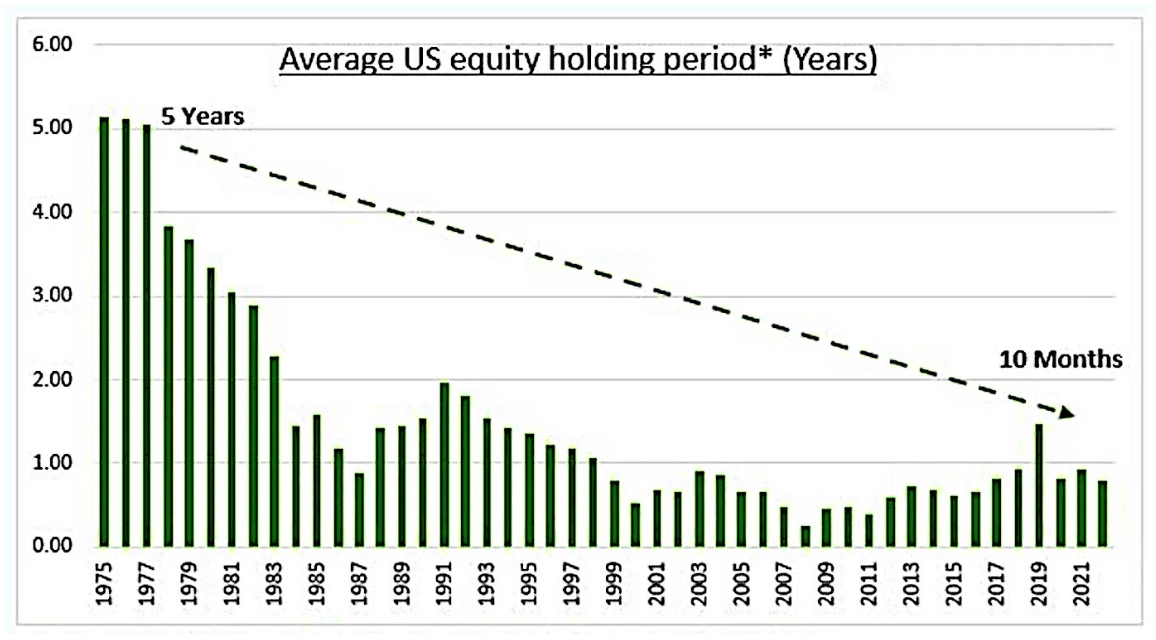

The trend is evident in the shrinking average holding period for stocks. According to eToro, the average holding period for US stocks has dropped to just 10 months, down from over five years in the mid-1970s, reflecting increased investor wariness about holding investments for too long, particularly during volatile periods.

Corporate longevity is also in decline

While short-termism among investors is not new, what has changed is that business life cycles are also shortening.

Consequently, stock index turnover is increasing as companies are being added to and removed from stock indexes more frequently, contributing to a declining average holding period.

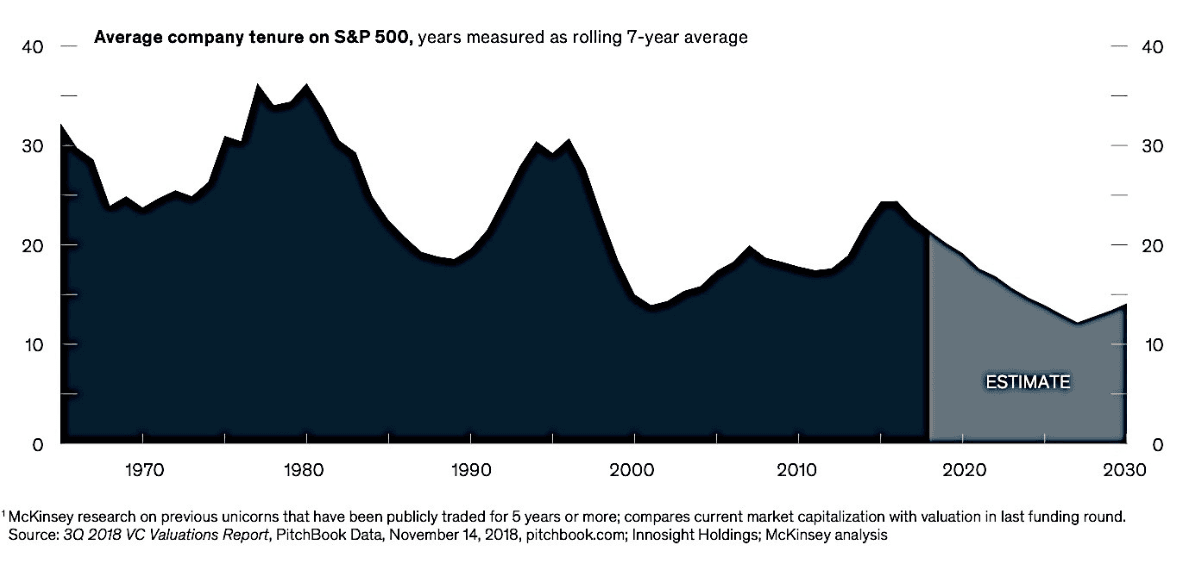

Research from McKinsey highlights this shift. In 1970, the average tenure of companies in the S&P 500 was 35 years. By 2018, this had dropped to 20 years, and projections suggest it could fall below 15 years by 2030.

Additionally, a PwC study found that the average CEO tenure in Australia has decreased from eight years to five years, reflecting a greater emphasis on short-term incentives among management teams.

The rise in shorter CEO tenures and rapid business changes suggests a growing incentive to pursue shorter term business results. This shift can lead to unstable management and frequent strategy changes, pushing investors to rethink their plans and consider the risks as short-term performance becomes more important.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

Long-term investing is not without risks

History suggests that staying invested over the long term increases the chances of a positive outcome.

A longer investment horizon can reduce the risk of loss, make it more likely to achieve the ‘average return’ (e.g.: the S&P 500 has delivered an average annual return of 10% p.a. over the last century), and even enable investors to benefit from market fluctuations.

Yet, a passive, buy-and-hold strategy isn't without its risks. In fact, it can increase the risk of significant losses over time. A US study using 100,000 simulations with the Black-Scholes model found that while the likelihood of losing money decreases with a longer horizon, the worst-case scenario (i.e. the potential for the biggest loss) actually worsens. So, while a 15-year horizon improves your chances of positive returns, a string of bad luck could still result in substantial losses.

Hence, what happened in the Japanese stock market could occur in other markets where unexpected economic events or structural shifts could lead to prolonged underperformance.

The challenge with long-term investing is that it assumes past performance will continue, which isn’t always the case. That’s why intermittent rebalancing may be helpful. Although it may seem counterintuitive to sell assets that are doing well to buy those that aren’t, rebalancing can help lower the risk of a significant portfolio hit from an outsized position.

Moreover, while long-term investing is often seen as safer due to the benefits of compounded returns, it may not be suitable for all investors, especially those nearing retirement or those without a long term investment horizon, particularly if they are uncomfortable bearing significant fluctuations in their portfolios.

Consider managed funds when investing for the long term

When it comes to investing in funds for the long term, index funds (ETFs) are popular among investors for maximising long-term returns. They provide easy, low-cost, liquid access to a vast array of global indices and sectors.

According to research by Neuberger Berman, actively managed funds also provide significant benefits for long-term investors, especially when assessed across various market cycles. The study, covering January 1999 to December 2018—including both bull and bear markets such as the technology and financial bubbles—shows that active funds often outperformed their benchmarks.

Unlike passive investments, which track the performance of a benchmark index whether it rises or falls, active funds can implement risk management techniques to shield portfolios during market downturns.

Flexibility is a super-power

While long-term investing offers significant potential benefits, it’s not without its complexities. Investors focusing on the long term should recognise that adaptability and periodic adjustments may be advisable on occasion, rather than rigidly sticking to a ‘buy and hold’ strategy.

After all, buy-and-hold investing doesn’t mean setting and forgetting. Understanding market realities and being prepared to reassess your portfolio can help navigate uncertainties and align with your long-term investment goals.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Ankita Rai. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.