Investing in the Age of Discontent

Simon Turner

Wed 4 Feb 2026 7 minutesIf you’re a news reader, you’re probably feeling like the world is engulfed in a crisis with no end date in sight. It sure feels like that as bad story after bad story is channelled toward news consumers around the world. Take your pick of which one matters most. Trump’s latest offensive tweet, the housing shortage, the cost of living, the system, the list goes on.

This is all happening whilst global macro data tells a very different story of a world defined by growing wealth, less poverty, and better healthcare outcomes. Despite these generally positive evolutions, it’s hard to argue with the fact that people en masse are angrier than ever before.

This is an important point for investors to understand when trying to make sense of markets which are no longer neatly explained by the usual macro indicators.

A Glaring Expectations Gap

Markets tend to be remarkably good at pricing in the future, most of the time.

But what happens when investors’ subjective impression of reality starts to diverge from a more objective version because they’re wearing jade-coloured glasses?

If that’s the case, as it appears to be of late, it may be that this collective global discontent is transitioning from a social story into a market pricing issue which is impacting the rules of the investing game.

The fundamental issue here is that people don’t benchmark their wellbeing against the human population’s wellbeing in the 1970s, or some other date in the distant past. They benchmark it against what they think they were promised, and against the lives they see around them.

Political scientists have long described this as ‘relative deprivation’, a perceived discrepancy between what people feel entitled to and what they believe they can achieve.

In a world in which most of us are constantly comparing our position with those of others (thanks in part to social media), rising expectations are outpacing rising incomes and net worths.

It’s Similar Albeit Slightly Different in Australia

Australia is an interesting example of this global trend, albeit one in which there’s been a closer match between reality and perception than in many countries.

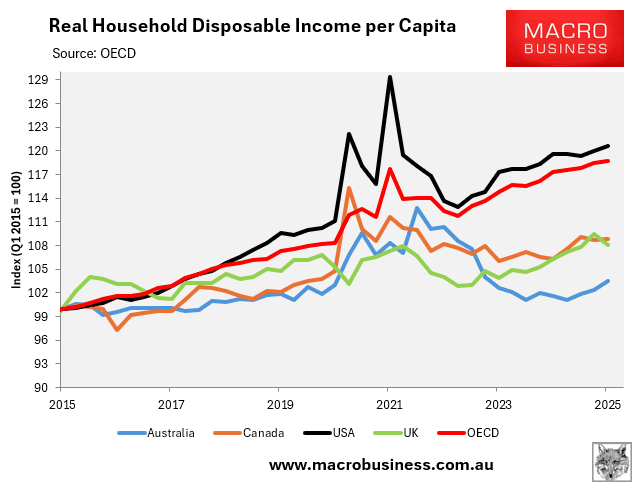

Real household disposable incomes have risen over the long-term, although the trend has turned decidedly negative since the pandemic. More importantly, from a comparison perspective, the OECD average is now higher than before the pandemic, and has significantly outperformed the Australian numbers.

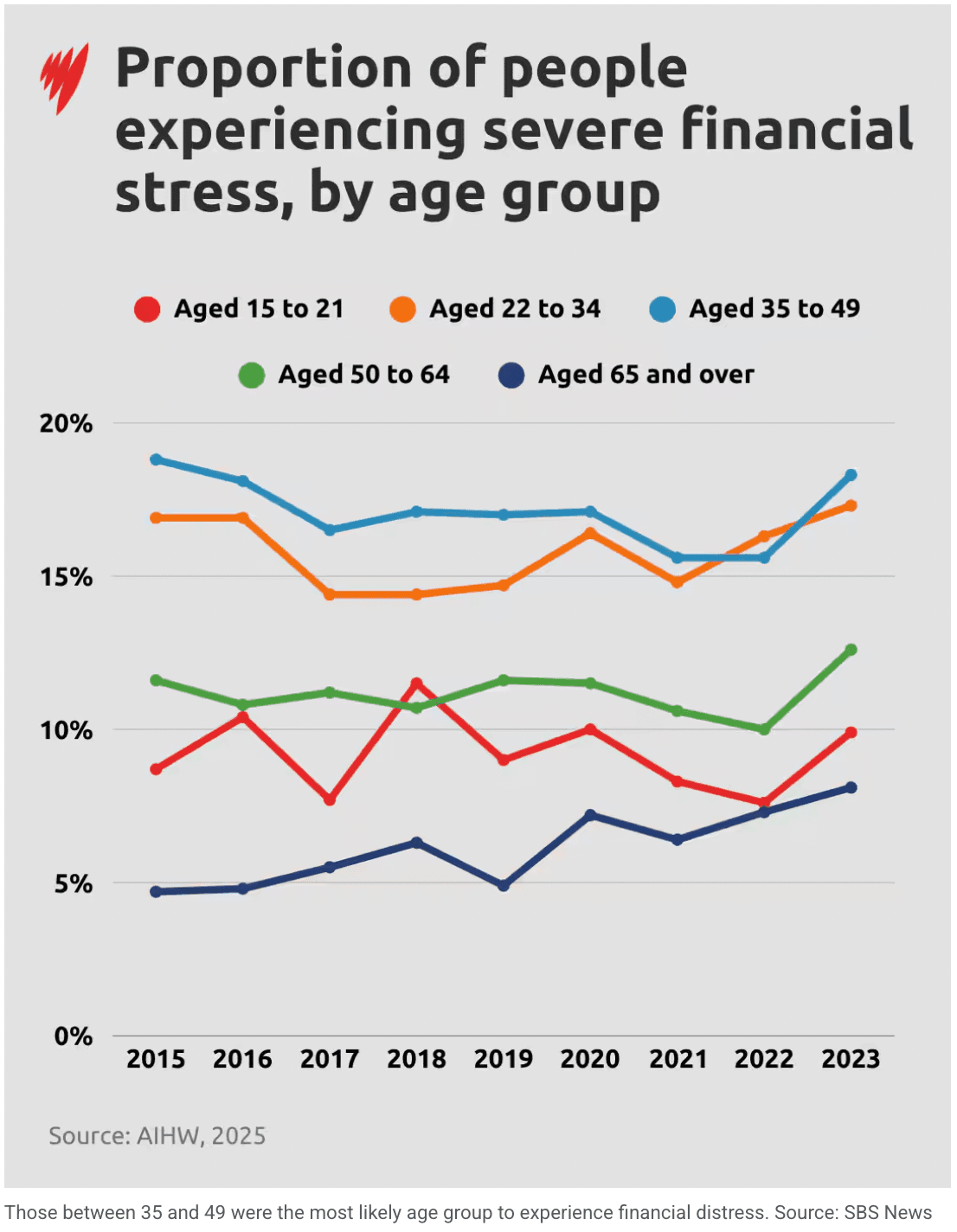

True to the global trend, household stress levels are rising in Australia, particularly since 2021.

This speaks to the comparison and regency bias that’s at the heart of the age of discontent. Australian household disposable income has recently taken a hit on both an absolute and relative basis, so the improving long-term trend isn’t front of mind for most people.

The majority are benchmarking their financial wellbeing against what they think they were promised, and against the lives they see around them: in this case, the rest of the developed world.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

The Clustering of Resentment

Now, let’s delve into where the above-mentioned stress and resentment tends to cluster.

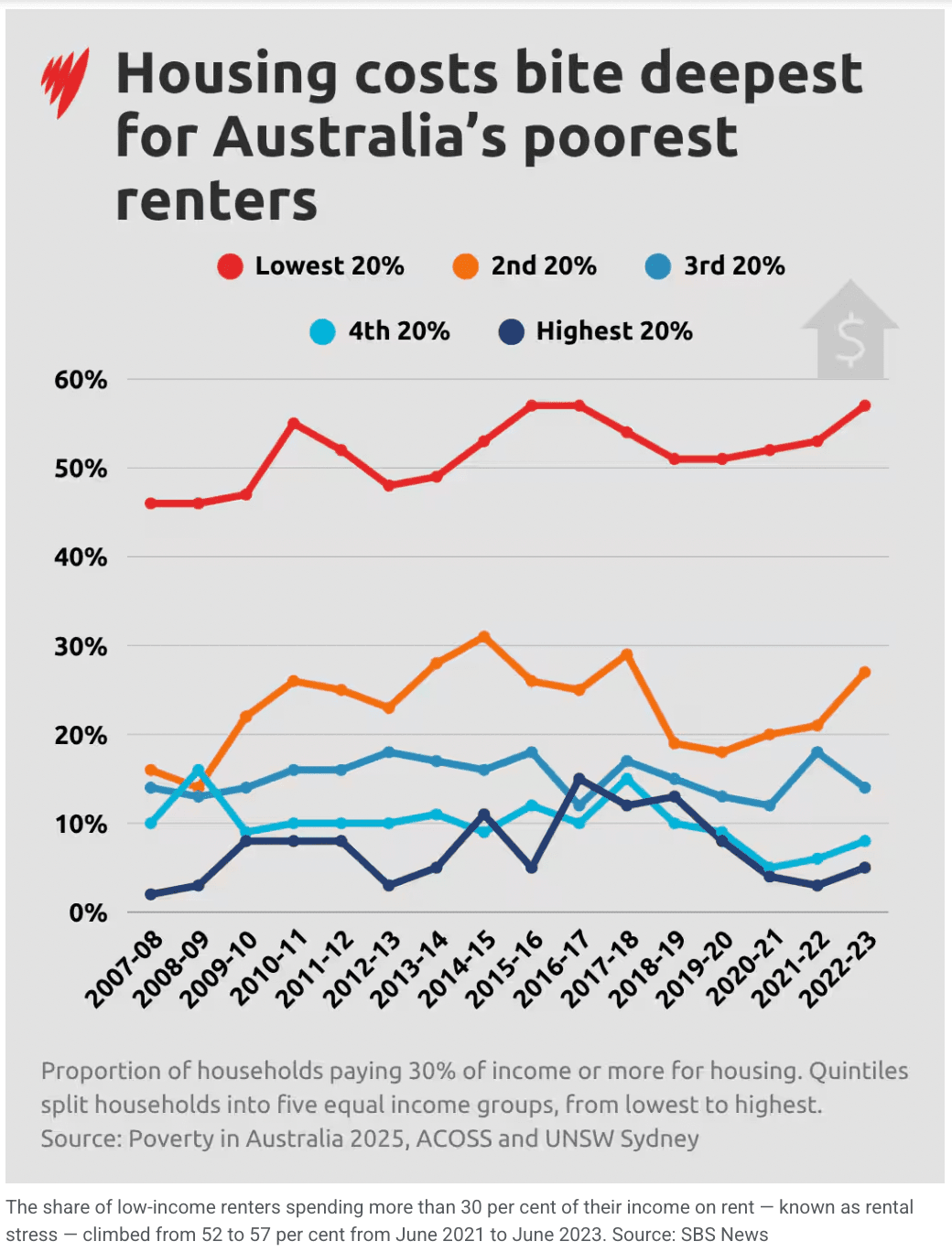

First, housing. When the cost of the ‘entry ticket’ to the dream of home ownership rises faster than wages, many people experience it as a broken promise, even if their consumption basket is objectively fuller than past generations. So housing is an area which attracts a lot of discontent for those who aren’t on the ladder yet.

Second, education and its old-school perception as a ‘mobility engine’. Recent research suggests that the university wage premium may be a thing of the past, and that educational standards and their signalling have deteriorated, turning what felt like a near-guaranteed pathway to a successful career into a riskier bet. That’s a source of resentment for many younger people who feel betrayed by the system.

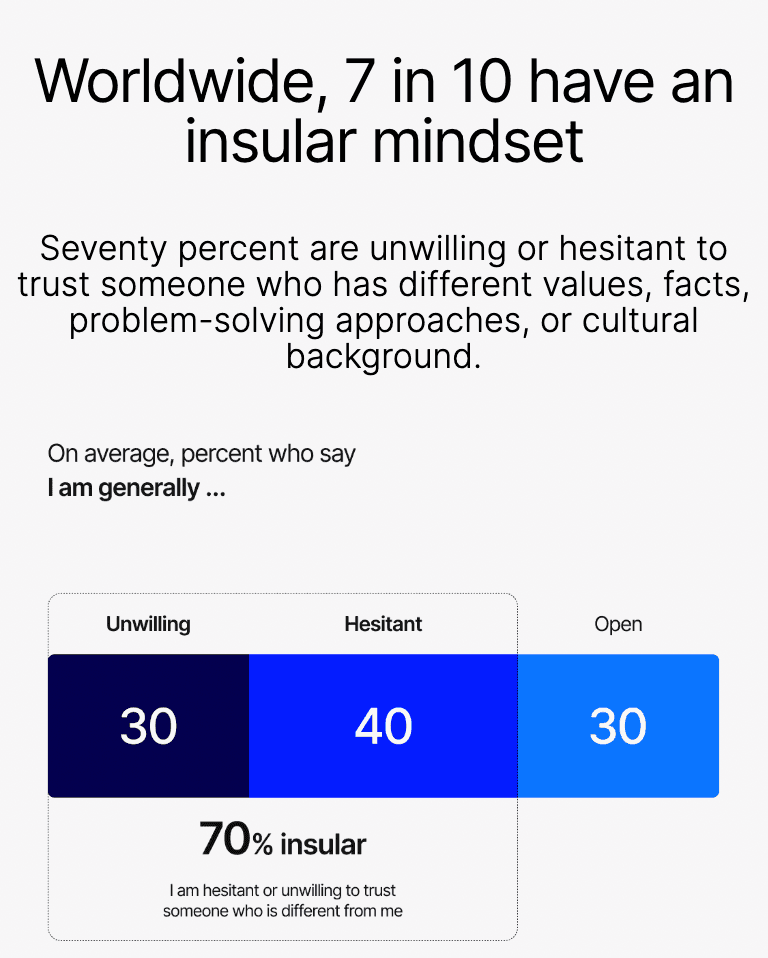

Third, trust. Low trust is rocket fuel for populist policy. Edelman’s 2026 Trust Barometer shows there’s been a marked shift from grievance to insularity, with a large portion of the global population reluctant to trust those who are different to them, and with widening trust gaps between higher- and lower-income groups.

All this points to one likely sociological direction: a lower-trust world with more policy surprises, higher risk premia, and more frequent market regime shifts.

In other words, buckle up.

Subscribe to InvestmentMarkets for weekly investment insights and opportunities and get content like this straight into your inbox.

The Investment Implications

So what does investing successfully look like in the age of discontent?

There are three important investment implications to be aware of:

1. Treat political risk as structural, not cyclical.

With the social challenges building, the global policy backdrop is likely to keep oscillating between intervention, regulation, and adaptive industrial strategies.

This backdrop favours portfolio construction that’s robust to multiple market regimes rather than optimised for a continuation of a single outcome.

In practice, that means global diversification may generate better risk-adjusted returns than a portfolio focused on the Australian market, or any home market for that matter.

For example, ETFs such as Vanguard MSCI International Shares ETF (ASX: VGS) provide low-cost, well-diversified exposure to global equities. And if you’d like to manage your currency risk, currency-hedged global ETFs such as JP Morgan Global Select Eq (Hdg) Act ETF (ASX: JHLO) provide exposure which is hedged back to AUD.

2. Time to hedge against policy-driven inflation and fiscal dominance risk.

Discontent often expresses itself through expensive fiscal promises that require a step-change in government spending. Even when governments do the right thing socially, markets may still demand compensation for the larger deficits, tighter labour markets, or supply-side constraints that are par for the course these days.

And the higher inflation associated with this direction of events is likely to impact which sectors out- and under-perform in the coming years.

So building portfolio resilience against this risk is arguably more important than ever.

That means investing in funds and ETFs positioned to thrive irrespective of macro developments, and which are protected against inflation.

For example, iShares Government Inflation ETF provides inflation protection by investing in a portfolio of Australian inflation-linked government bonds. Gold is also a classic hedge against inflation as well as policy error, geopolitical shocks, and a loss of confidence in institutions. ETFs such as Global X Gold Bullion ETF (ASX: GXLD) and iShares Physical Gold ETF (ASX: GLDN) provide diversified exposure to this sector.

3. Back the real economy capex that governments will subsidise regardless of ideology.

When societies are unhappy, politicians often rollout headline-grabbing projects to steady the ship in areas such as: energy security, grids, ports, defence supply chains, local manufacturing, housing, infrastructure, and climate change adaptation and mitigation projects.

Investors can benefit from this trend by investing in funds and ETFs focused on infrastructure and commodities.

For example, ETFs such as iShares Core FTSE Global Infrastructure (AUD Hedged) ETF (ASX: GLIN) provide exposure to infrastructure, while BetaShares Energy Transition Metals ETF (ASX: XMET) provides exposure to the producers of metals used in electrification and decarbonisation.

A Macro Factor with Significant Market Implications

The age of discontent has surely arrived. It’s showing up as policy volatility, trust erosion, and shifting fiscal priorities. Moreover, it’s the underlining reason so many investors are cynical these days.

It may be that the most prudent response is building portfolios that assume the social temperature remains high and volatile. Globally diversified equities, commodities and real assets are likely to outperform if that scenario continues to play out longer term.

Funds Mentioned

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.