Is it Time to Worry Like Ray Dalio?

Simon Turner

Mon 12 Jan 2026 7 minutesRay Dalio has spent much of the past decade warning that investors are misreading reality. Markets, he argues, are telling one story in nominal terms and a very different one in real money terms. Asset prices may be rising, portfolios may look healthy, and indices may be hitting new highs, but measured against the true store of value, purchasing power, many investors are quietly going backwards.

For years, his arguments were easy to dismiss. Inflation appeared contained, central banks seemed to be in control, and equity returns were strong enough to overwhelm most investors’ theoretical concerns about currency debasement. But last year, everything changed. The currency backdrop shifted decisively, valuation buffers thinned, and the gap between perceived wealth and real wealth widened in ways that even complacent investors couldn’t ignore.

The question now confronting investors isn’t whether Dalio has been directionally right. That’s beyond debate. It’s whether his framework implies something materially different for portfolios as the new year begins. Should you be worrying like Ray Dalio?

The 2025 Currency Reality Check

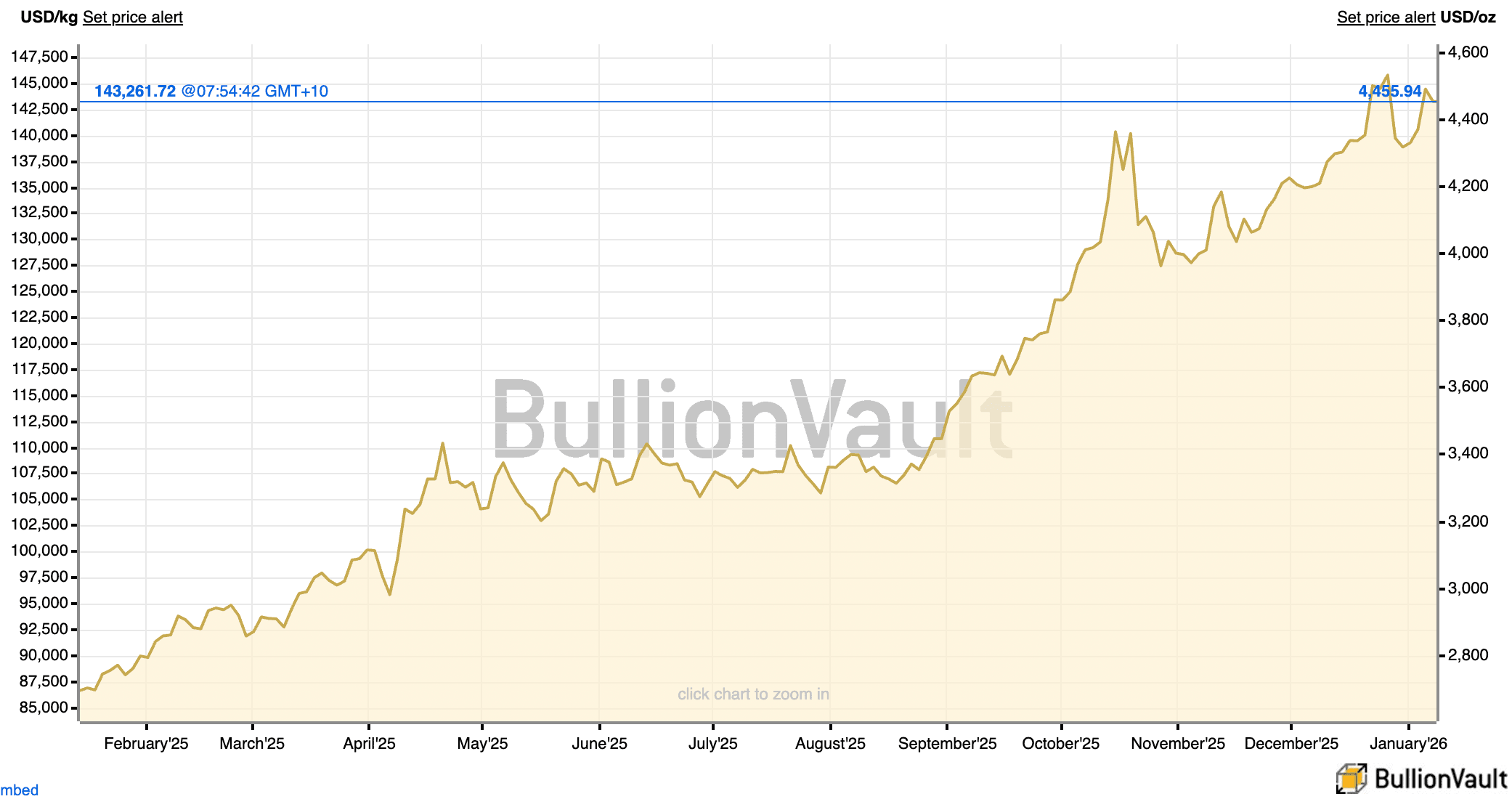

Dalio’s insistence on evaluating returns through a currency-adjusted lens has rarely been more relevant than in 2025. Headline equity returns masked a more important story underneath. The U.S. dollar weakened meaningfully across almost every reference point that matters. It fell modestly against the yen and the Aussie dollar, more substantially against the renminbi, euro and Swiss franc, and catastrophically against gold.

Gold deserves special attention in this context. It’s not simply another commodity or inflation hedge. It’s the second-largest reserve asset in the world and the only major monetary asset that isn’t someone else’s liability. So when gold rises sharply against fiat currencies, it isn’t making a directional call on growth. It’s issuing a verdict on the value of fiat currencies as investors selectively reprice credibility, discipline, and balance sheet integrity.

This backdrop produced an uncomfortable result for investors in U.S. stocks last year (read: most global investors). In U.S. dollar terms, the S&P 500 delivered a respectable 18% return. But in gold terms, the index fell by 28%. So the best major investment of the year wasn’t the Magnificent 7. It was owning gold and gold stocks.

Dalio’s point isn’t that equities are uninvestable when local currencies are devaluing like this. It’s that measuring success purely in nominal currency terms can lull investors into a false sense of security. In short, a rising portfolio doesn’t necessarily mean rising purchasing power.

For Australian investors, this framing is especially important. Australia is a small, open economy with a structurally volatile currency. When global capital shifts, the Aussie dollar tends to move sharply, amplifying gains in good times and losses in bad. So ignoring currency isn’t a neutral strategy with benign outcomes. It’s an active bet with significant portfolio ramifications.

Valuations & the Limits of Optimism

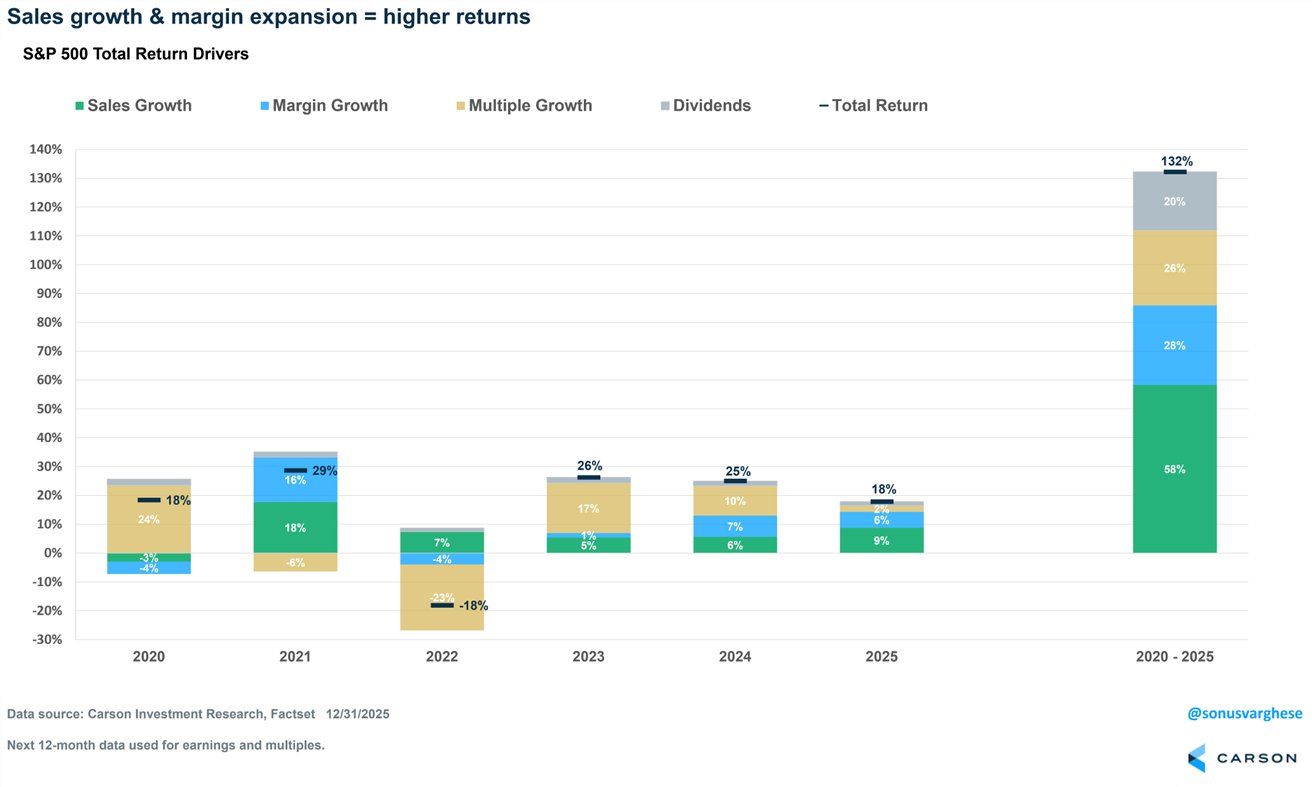

Currency weakness alone doesn’t end bull markets. What concerns Dalio more is the concurrence of a weakening U.S. currency and valuation extremes in such a globally dominant market. That said, U.S. equities delivered strong local currency returns in 2025 because three things went right at once: earnings grew at a healthy pace, valuations expanded modestly, and dividends contributed positively. That combination is powerful, but it’s unrealistic to expect it repeat every single year. 2022 was a good example of what happens when those drivers reverse, as shown below.

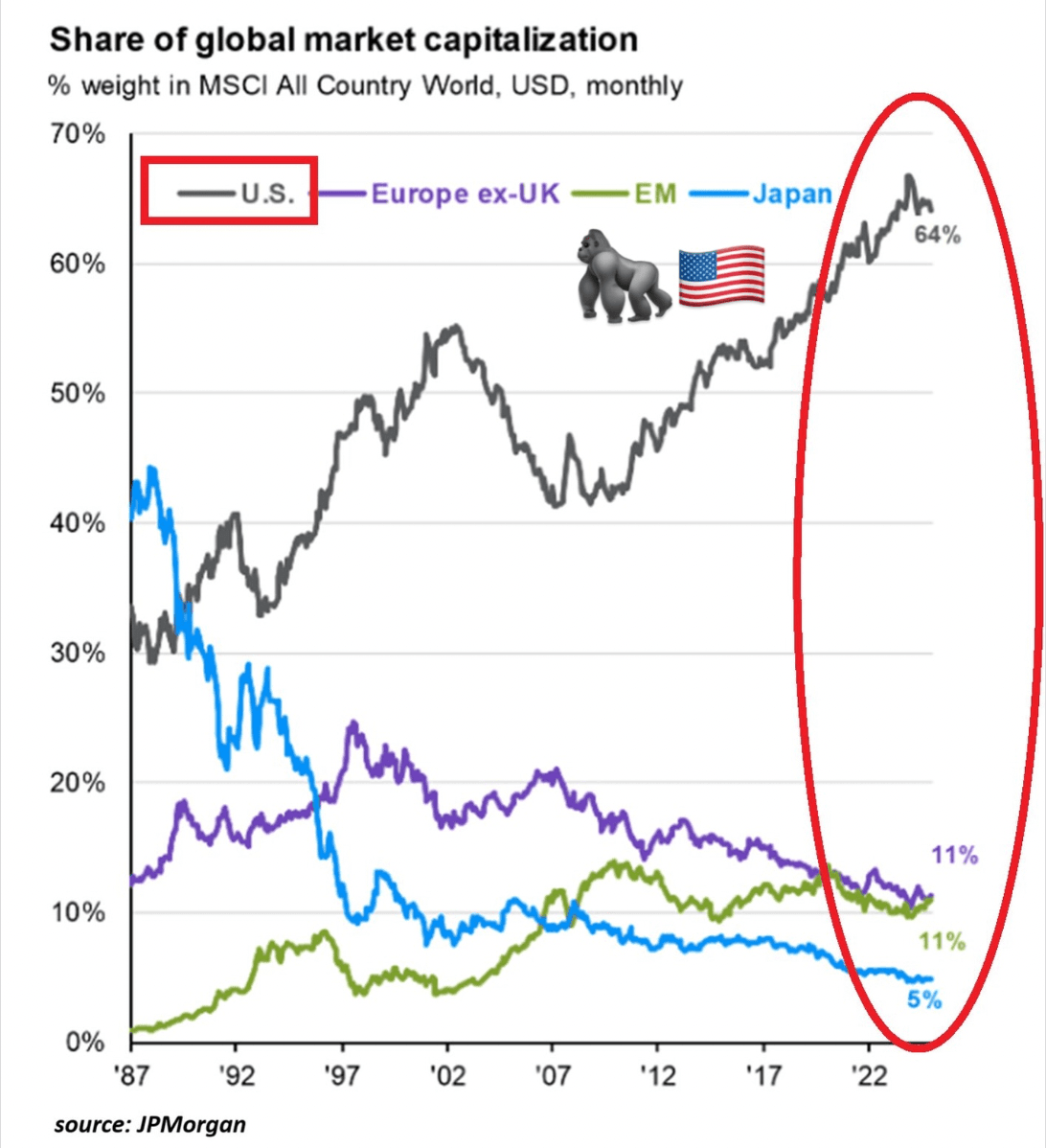

Looking forward, the arithmetic becomes less forgiving. Valuations are elevated by historical standards, credit spreads are tight, and equity risk premiums are thin. Most analysts now expect long-term U.S. equity returns to be below bond yields. That inversion should make investors pause. It implies that the margin for disappointment is small and the sensitivity to shocks is high. That’s potentially a significant issue for most global investors given the U.S. represents an incredible 64% of the MSCI World Index.

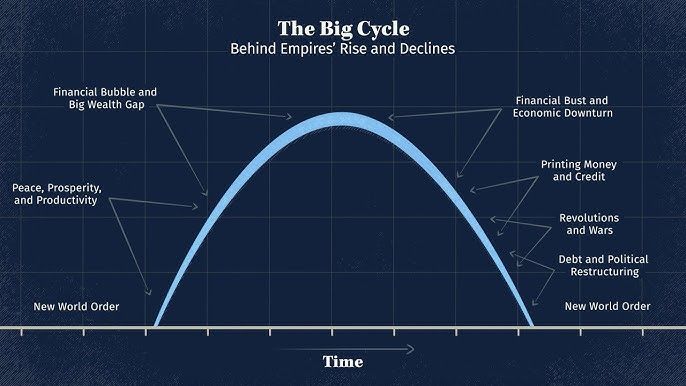

Dalio situates this within his broader ‘Big Cycle’ framework (see below), which views markets as shaped by the interaction of debt, money, politics, geopolitics, nature, and technology. The critical insight is not that any one of these forces is deterministically bearish. It’s that when several reach extremes simultaneously, the probability of regime change rises.

From this perspective, the start of 2026 looks less like the beginning of a crisis and more like the late stages of a long expansion. Liquidity remains abundant, developed market fiscal deficits large, and asset prices heavily supported. But whether those supports can continue indefinitely without further debasing of currencies or triggering political backlash is surely less certain at this juncture.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

Translating Dalio’s Philosophy into Resilient Portfolios

Worry isn’t a useful strategy. But neither is complacency. Dalio’s framework doesn’t imply investors should exit markets in the face of an imminent collapse. It suggests that they reassess their market assumptions formed in a very specific historical period.

Case in point: the past decade rewarded concentration in U.S. equities, tolerance for valuation expansion, and indifference to currency risk. That combination worked well because inflation was subdued, geopolitics relatively contained, and central banks credibly committed to asset price stability.

None of those conditions can be taken for granted now.

For Australian investors, these risks are compounded by home market bias. Australian equities are heavily concentrated in banks and resource companies, both of which are sensitive to global cycles and China-linked demand. The Aussie dollar is similarly pro-cyclical. So a portfolio that’s overly domestic is implicitly doubling down on a single macro outcome.

Dalio’s answer to this is not prediction, but resilience. He argues for building portfolios that can survive multiple environments, including inflationary shocks, currency debasement, political instability, and geopolitical fragmentation. That inevitably leads to greater diversification across regions, asset classes, and currencies.

Gold plays a central role here, not as a speculative bet, but as insurance. It performs when confidence in money erodes, when debt is monetised, or when political incentives overwhelm fiscal discipline. Owning some gold is an admission that no policymaker has perfect control.

A Dalio-aware portfolio for Australian investors departs meaningfully from the traditional balanced fund.

Rather than assuming benign global growth and a perpetually strong U.S. dollar, it explicitly manages currency risk, reduces dependence on U.S.-centric outcomes, and retains structural hedges even in growth-oriented portfolios.

For conservative investors, the priority is purchasing-power preservation: Australian equities are capped despite franking benefits, allocations favour inflation-linked and short-duration bonds, gold is held as strategic insurance, and some cash sits in foreign currencies.

Balanced investors shift their focus from asset labels to economic resilience, keeping Australian equities below market weight, tilting global equities toward Europe, Japan and selective emerging markets, using bonds for stability rather than yield, and treating gold as a permanent allocation.

Even aggressive investors, in Dalio’s framework, avoid fragility. Growth is sought through diversified global equities rather than domestic concentration or single narratives like U.S. mega-cap technology, gold is reduced but not eliminated, and alternatives are used to diversify return drivers rather than amplify leverage.

The unifying principle is avoiding dependence on one country, one currency, or one policy regime.

Should you Worry like Ray Dalio?

No, you shouldn’t worry like Ray Dalio. Awareness is the better response. Dalio is not predicting the end of capitalism or the imminent collapse of fiat money. He’s just highlighting that the conditions which made recent U.S. market returns feel effortless are unlikely to persist unchanged.

The practical takeaway is that measuring success purely in local currency terms is no longer sufficient. Concentration risks are higher than they appear, valuations offer less protection than they used to, and currency dynamics matter again.

The opportunity is not to sell everything, but to develop more resilient portfolios which are positioned to thrive in multiple macro scenarios. Ray Dalio’s real warning is not that something bad is about to happen. It’s that pretending nothing is ever going to change is the most dangerous position of all.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.