Where the inflation monster does most of its work

Simon Turner

Thu 9 Nov 2023 8 minutesThe recent Australian Consumer Sentiment Snapshot reveals Aussie consumers have one particular economic factor front of mind… inflation.

The inflation monster is impacting upon consumers’ disposable incomes, and more importantly it’s causing havoc in consumers’ minds where it’s doing most of its insidious work. It’s this growing awareness and fear of inflation which suggests we may be on track for inflation to trend higher than markets (and central bankers) currently believe. If that is indeed the case, the investment implications are significant…

The inflation monster is scaring the locals

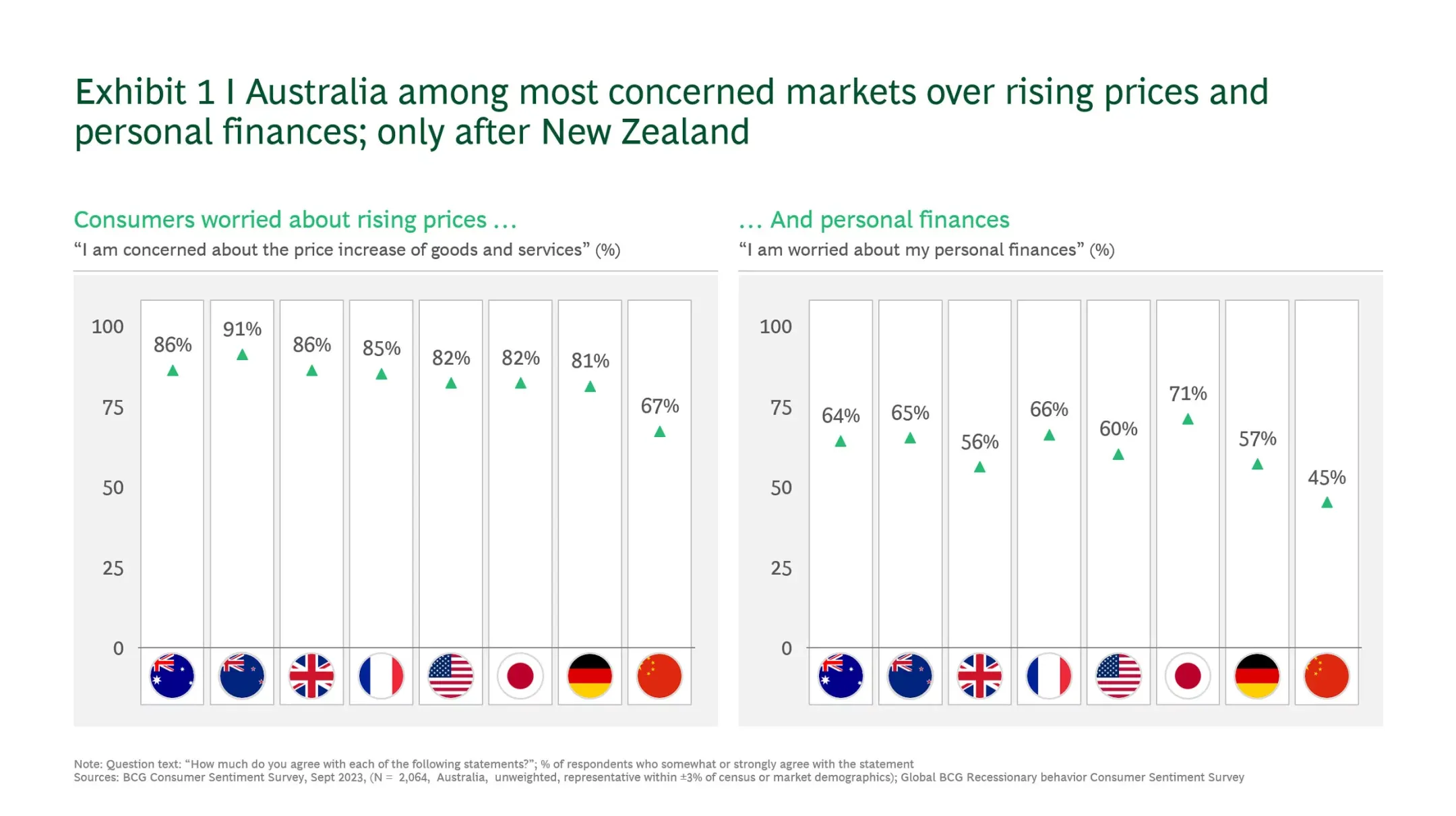

As shown below, a massive 86% of Australia consumers are concerned about inflation, which is above the global average of 81%. Of developed market consumers, only New Zealanders are more worried about it (before you ask, that statistic predated New Zealand’s Rugby World Cup loss).

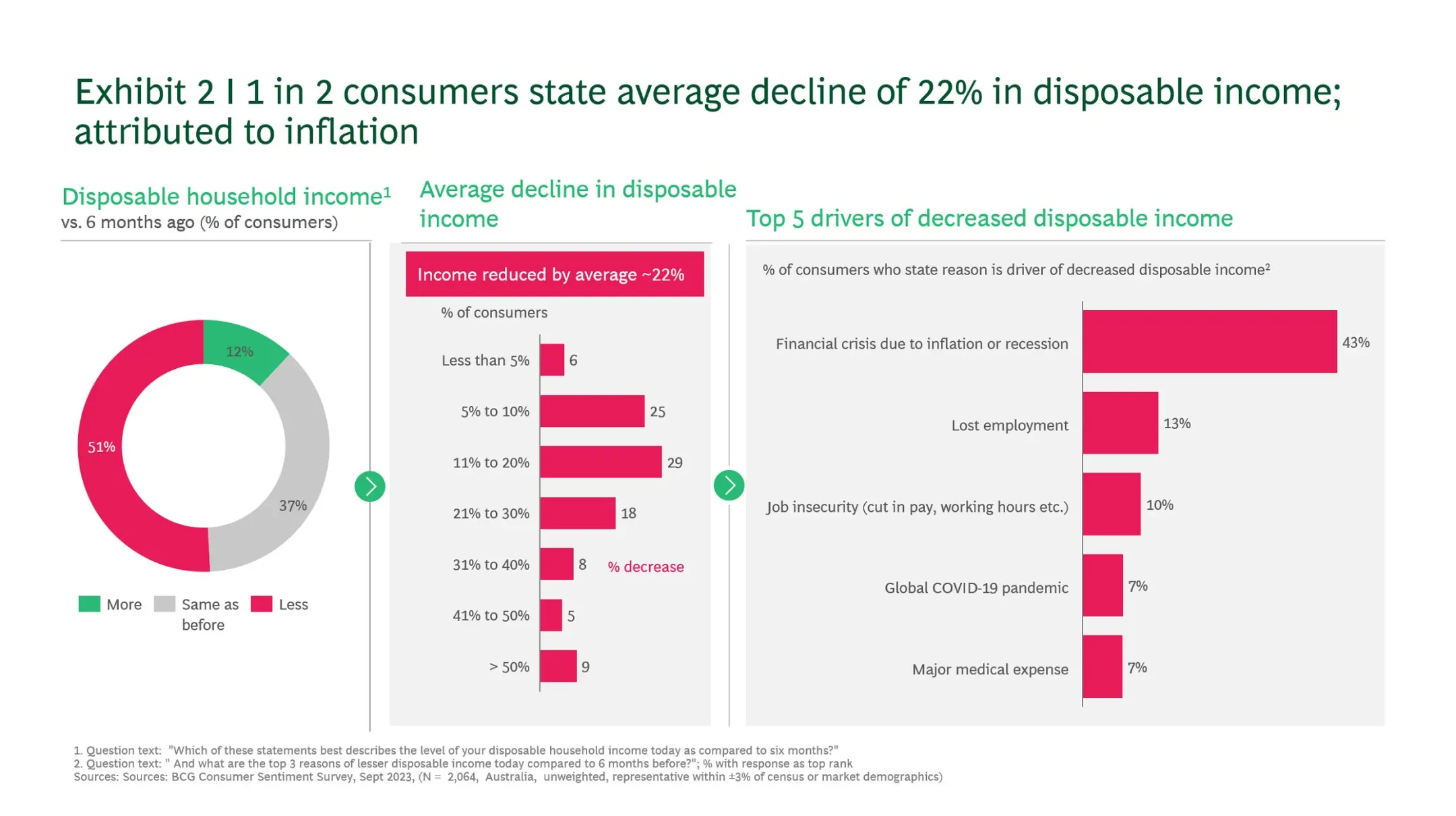

Aussie consumers appear to be feeling the effects of inflation particularly acutely. As shown below, average disposable incomes fell 22% over the six months to the end of September. That’s a remarkably sharp drop over a six-month period.

What’s most interesting about this survey is the high degree of awareness amongst Aussie consumers of what’s driving their disposable incomes lower.

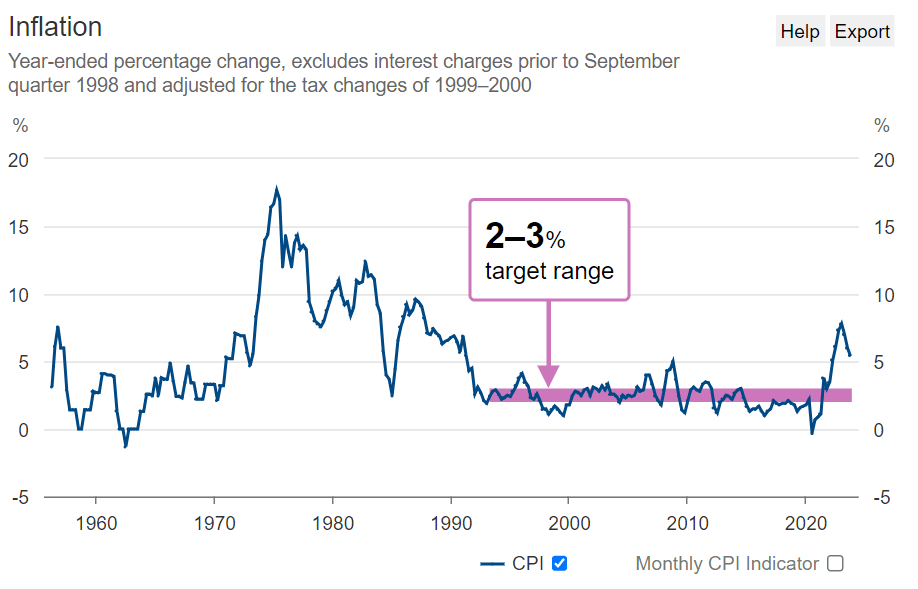

Inflation remains above the RBA’s target range

Despite the RBA’s thirteen rate rises, inflation is still running well above its targeted range of 2-3% p.a. As shown below, inflation was 5.4% during the year to September. That’s high in the context of the past three decades, but low versus the 1970s when inflation ran into the double digits.

A psychological force which appears to have a mind of its own

Inflation is a strange and often misunderstood beast. We recently wrote an article arguing that central bankers may not be controlling the inflationary strings as much as they’d like investors to believe. We highlighted that the main source of inflation may in fact be corporate profiteering…

'The term ‘escuseflation’ has emerged to describe how the corporate world has justified higher prices in recent years as an apparent strategy to pass on rising costs to consumers. Despite these excuses, there’s no hiding the fact that corporate margins keep rising. In fact, US corporate margins hit a 70-year high last year.’

High consumer awareness of the inflation monster’s presence combined with this corporate profiteering may help provide a clue as to what’s coming next. In fact, history provides a valuable guide of the way memory reawakening drives inflation higher.

You just need to ask a group of baby boomers about inflationary pressures in the 1970s and you’ll receive impassioned feedback about how challenging that period was. Even those who are too young to have lived through the 1970s have short-term memories of the challenges of living in an inflationary world thanks to the pandemic.

Memory reawakening of inflation compounds every time we go to the supermarket. It’s as simple as seeing a product that’s increased dramatically in price and reminiscing on how fast things are changing. For example, you may notice your favourite deodorant is selling for $9 whereas you remember buying it for $5 less than a year ago.

These minor data points compound in our minds and awaken the feelings we experienced when inflation previously reared its ugly head in our lives. These feelings usually include stress and inspire questions in our minds like: Will I be able to afford a similar lifestyle if this continues? And they drive consumers to alter their behaviour by bringing forward purchase decisions in order to reduce their exposure to future inflation. This higher demand creates more inflationary pressure.

The inflationary narrative is being reinforced in consumers’ minds by the media and other economic agents. In fact, it’s already rare to read a news story which doesn’t highlight the downsides of inflation or the ‘replay of the 1970s’ narrative. These stories serve to add fuel to consumers’ existing fears about inflation. This is exactly the playbook via which structural inflation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. That’s why inflation is a deeply psychological force which often eludes central bank control.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

A case study in the emergence of hyperinflation: Weimar Germany

It may well be that the best thing investors can do at this juncture is to read The Economics of Inflation by Costantino Bresciani-Turroni. The book discusses the experience of hyperinflation which emerged in Weimar Germany between 1914 and 1923. Spoiler alert… it’s a cautionary tale.

Here’s a summary of what occurred during that remarkable period in history (some of these points may resonate with present day urgency):

Inflation peaked at over 200 billion per cent in 1923. Few saw this hyperinflation coming at the time, and many claimed its roots were unclear and unpredictable. In hindsight, we know it was caused by the rising cost of goods combined with a dramatic increase in the money supply which created the perfect conditions for hyperinflation to emerge.

Currency also played a key role. The German government was burdened with a large debt care of the Treaty of Versailles. With its gold reserves depleted, the government sold German marks to buy foreign currency, causing the mark to decrease in value. When the German people realised their currency was devaluing, they tried to spend it quickly which also fuelled inflation.

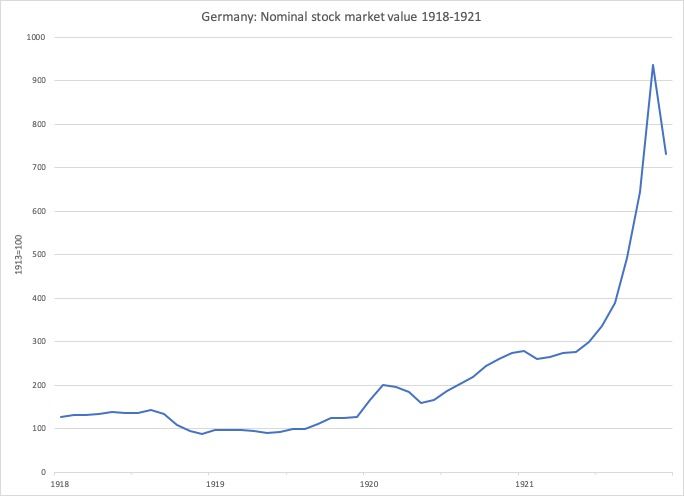

The equity market went parabolic during that period as investors realised equities provided the most effective protection against the wealth-destroying impacts of inflation. Check out the equity market returns between 1918 and 1922:

Despite the parabolic equity returns, there were sharp selloffs along the way. Even speculators who were bullish on the equity market due to the lack of inflation-protecting alternatives were often wiped out by margin calls and/or the extreme market volatility. Despite the challenges, large swathes of the population stopped working in favour of speculating on equities with margin loans because it was often more profitable than working a full time job.

On numerous occasions, the Weimar Government tried to arrest the hyperinflation but the economic and political pain was too extreme so they regressed to quantitative easing which in turn drove inflation (and equity markets) higher.

Hyperinflation was so distressing for German consumers at the time that some doctors believed it caused a mental illness which led to patients not being able to stop writing zeros.

Most economists would argue the likelihood of a similar episode happening today is low—but not impossible. More importantly, this case study provides valuable directional guidance of what to expect if inflation were to remain higher for longer: i.e. strong equity market performance combined with higher volatility.

Takeaways for investors

Being aware of the psychology of inflation and the lessons of the past could well prove fruitful for investors in the coming years. Here are the key takeaways to be aware of:

Growing global and local consumer concerns about inflation suggest it may be on track to become structural (higher for longer) in nature.

Central bank action may not prove effective at controlling inflation as intended. As such, if central banks resume raising interest rates in an ongoing attempt to control inflation the risk that they create and amplify broader economic challenges is rising.

For a guide as to what happens during periods of hyperinflation, we just need to look at the experience in Weimar Germany, a century ago. That historic episode showed that remaining invested in equities with strong pricing power was the most effective strategy to protect against the destructive effects of inflation. However, many investors weren’t able to hold onto their inflation-protecting stocks in the face of heightened equity market volatility.

Investors who believe inflationary risks lie on the upside may be well advised to focus on assets which have historically outperformed during periods of structurally high inflation – e.g. real assets such as property and commodities, and equities with strong pricing power.

The optimal strategy for a more inflationary world appears to be investing in equities and equity funds for the long term combined with dollar cost averaging during market selloffs to capture the benefits of market volatility.

Subscribe to InvestmentMarkets for weekly investment insights and opportunities and get content like this straight into your inbox.

Be ready in case history repeats

The recent Australian Consumer Sentiment Snapshot highlights that consumers are acutely aware that inflation is costing them a sizeable portion of their disposable income. The key point for investors is that this may be a harbinger of inflation remaining higher for longer. Arguably, it’s also a warning to investors to get ready for altered market conditions which are likely to confound shorter term investors who aren’t aware of the way structural inflation affects investment markets.

If history and an awareness of the psychology of inflation is to be used as a guide, we could be approaching a period of strong equity returns combined with heightened volatility. Rather than being fearful of the inflation monster, being ready for this scenario could be the difference that makes the difference for investors.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.