The U.S. vs the Rest of the World

Simon Turner

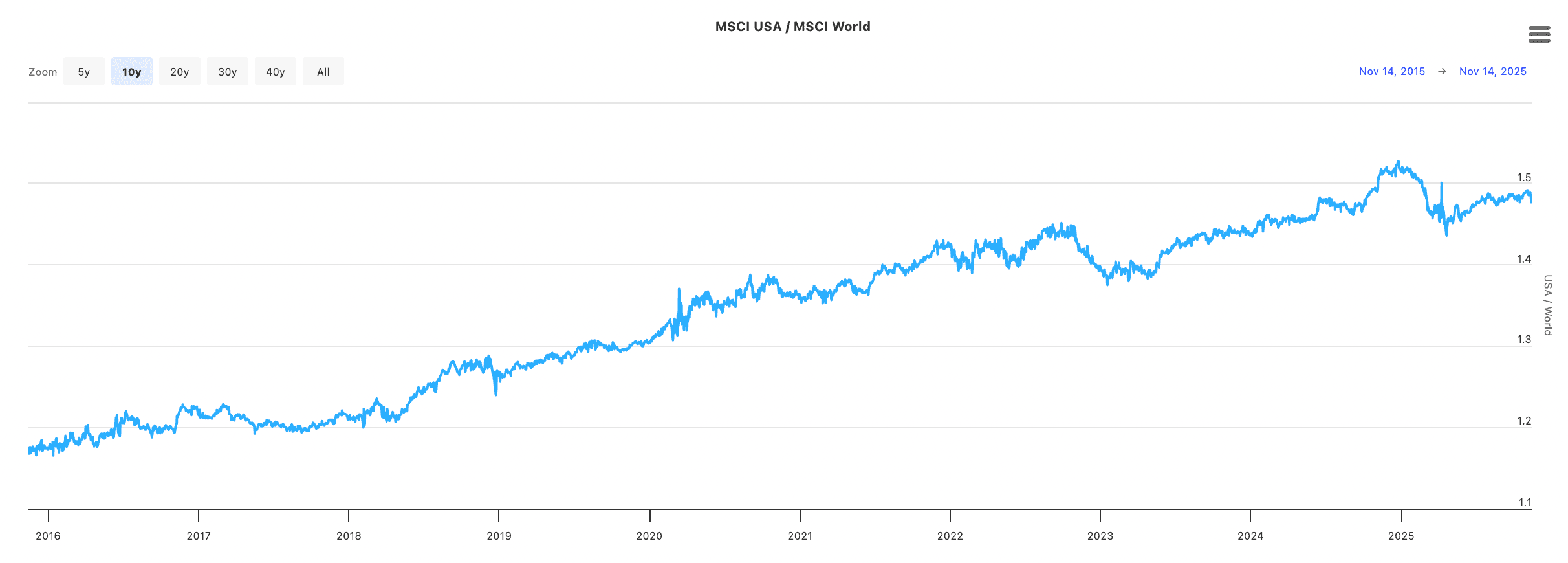

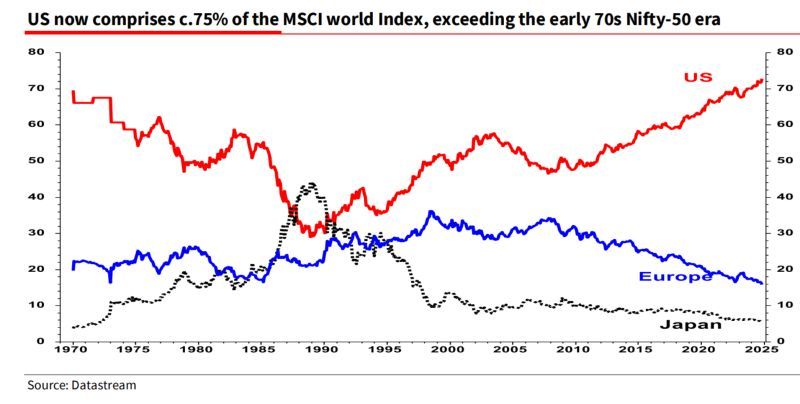

Wed 3 Dec 2025 6 minutesFor more than a decade, it’s rarely been wrong to be long U.S. equities. The numbers are hard to argue with: the MSCI USA index has outperformed the MSCI World index by almost 50% over the past ten years. The longer term data is even more stark: U.S. stocks have risen from 30% of the MSCI World Index in the 1990s to 75% today. For all intents and purposes, U.S. stocks now dominate global equities.

When new extremities are reached in investment markets like this, it’s generally wise to question whether they’re sustainable. So in this case, the question is: are US equities likely to continue outperforming, or is the rest of the world ready to play catch up?

We’ve Been Here Before

The rising dominance of U.S. equities has been one of the more consistent and structural trends at play in global investment markets over the past decade, as shown in the rising blue line below. This trend has been investors’ best friend throughout that period.

Whilst it may feel like the extent of U.S. dominance of global markets is a completely new phenomenon, it’s not. In 1970, U.S. stocks represented a similarly large portion of the MSCI World Index, as shown below.

Whilst this is useful context, having been here before is unlikely to give investors peace of mind given what happened in the ensuing couple of decades after the high in 1970 when U.S. stocks more than halved as a percentage of the MSCI World Index.

Explore 100's of investment opportunities and find your next hidden gem!

Search and compare a purposely broad range of investments and connect directly with product issuers.

The Tide May Be Turning

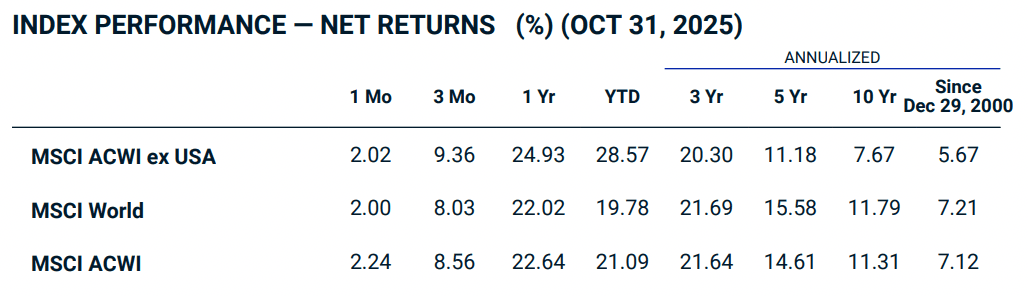

The consensual view that the U.S. is positioned for continued global outperformance has been tested in 2025. For the first time in a long time, international markets have outperformed the U.S. As shown below, the MSCI ACWI ex USA index is 9% ahead of the MSCI World Index year to date.

Of course, one swallow doesn’t make a summer. But could this could be the start of one of the most significant market rotations in recent decades?

The Shifting Sands of Valuation

Valuation is the most powerful argument that the next decade may look different from the last.

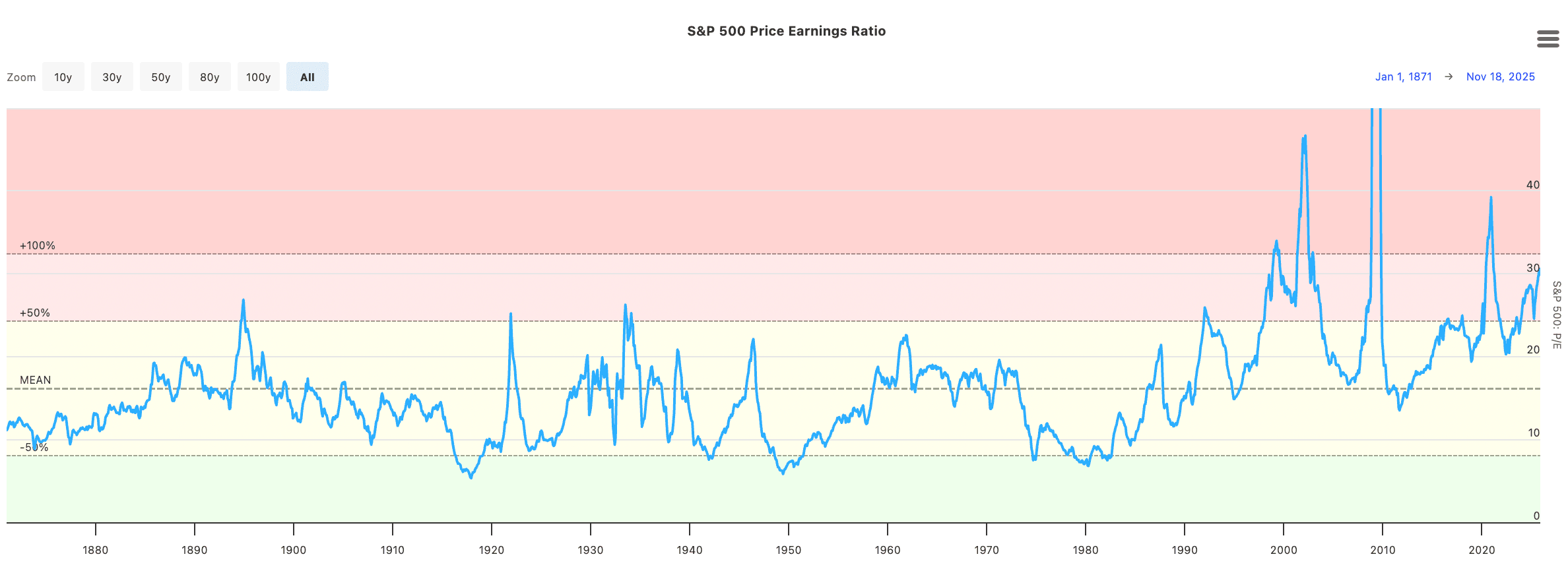

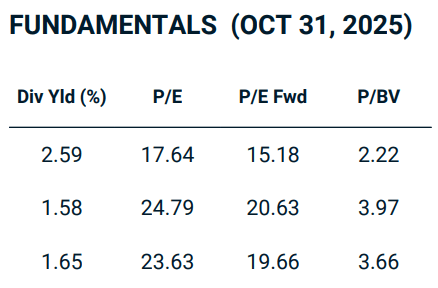

First, to the U.S., where the S&P 500 is currently trading at a trailing twelve-month P/E ratio of 29.87x, more than double its long term mean, while its dividend yield of 1.17% p.a. is also well below its long-term average of 1.8% p.a.

In contrast, the MSCI ACWI ex USA index is trading on a trailing P/E of 20.6x and a 1.6% p.a. dividend yield.

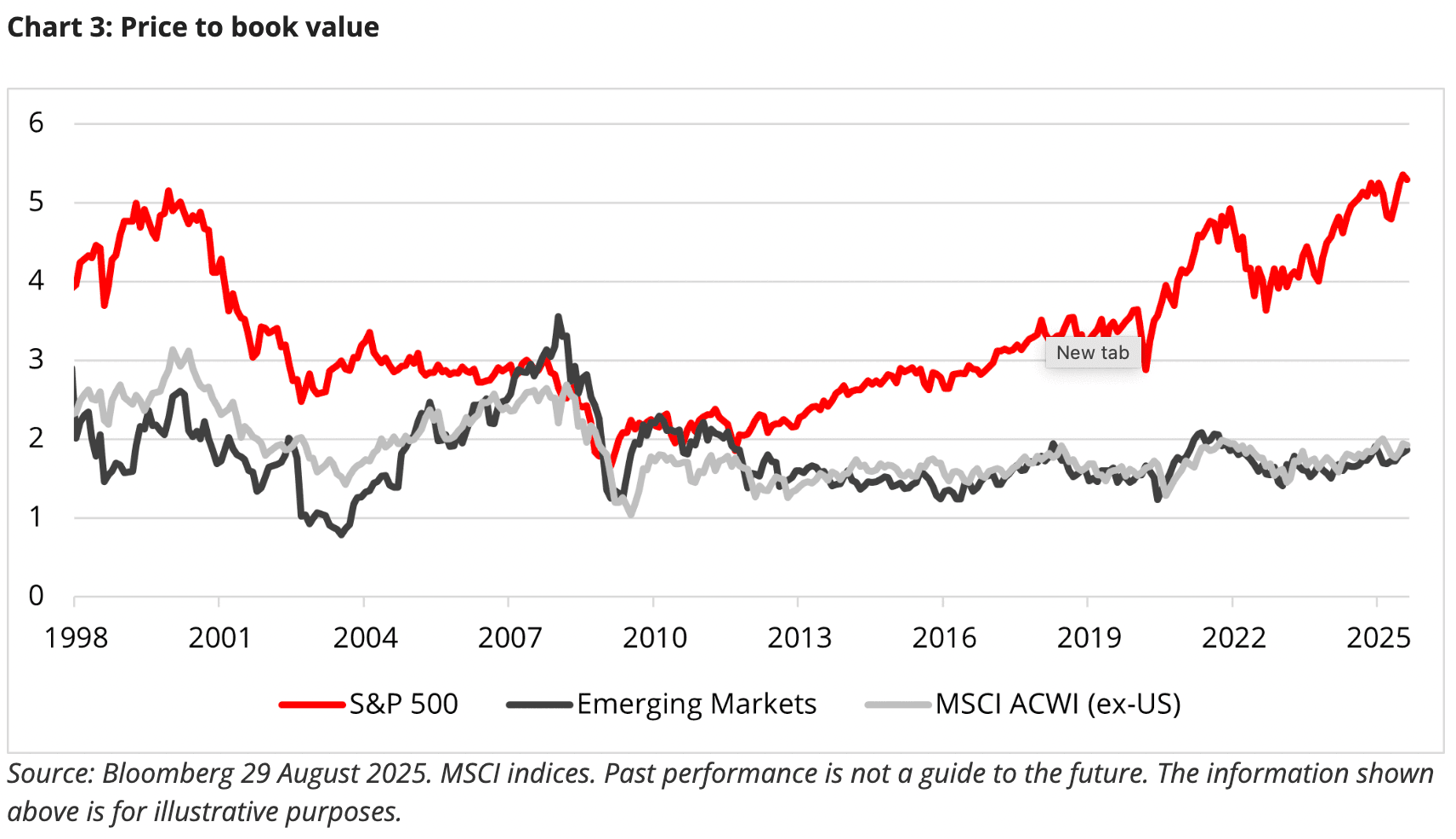

The difference is even starker on a price/book value basis, with the S&P 500 trading at more than double the multiple of the MSCI ACWI ex USA index.

This vast valuation gap reflects not only optimism about U.S. earnings but also the extraordinary build-up of global capital flowing into a narrow set of U.S. growth stocks, particularly the Magnificent Seven.

Of course, relative valuations between regions reflect differences in expected earnings growth and the associated risks. Whilst the U.S. has long led the rest of the world on this front, its consensual eps growth expectations of 13% in 2026 and 12% in 2027 are now almost identical to ex US global markets. So the arguments in favour of such a large U.S. valuation premium are arguably less convincing than they used to be.

Subscribe to InvestmentMarkets for weekly investment insights and opportunities and get content like this straight into your inbox.

The Productivity + Demographics Equation

A simple call for international outperformance of the U.S. would be lazy at this juncture.

Many of the reasons for U.S. strength remain in place and still matter.

Productivity has to enter the mix as a key consideration. U.S. productivity growth has outpaced other developed economies since the financial crisis and that advantage is expected to persist well into the coming decades.

The U.S. also enjoys more favourable demographic projections than most countries, at least under current immigration assumptions. Partly as a result, consensus earnings forecasts continue to show U.S. corporates are likely to continue generating higher profit margins than their European or Japanese peers.

Sector composition is another reason why U.S. valuations deserve some premium.

The American market is dominated by market leading stocks that sit at the heart of sectors positioned for structural growth such as artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and digital advertising.

It’s also worth remembering that for Australian investors heavily exposed to local banks and resources, U.S. equities offer exposure to parts of the global economy which can’t be accessed via the ASX.

Currency Also Plays a Role

Currency is another consideration. A global portfolio dominated by unhedged U.S. funds is effectively a bet on the U.S. dollar against the Australian dollar.

So if the U.S. dollar’s exceptional run of the past decade reverses, unhedged international holdings could enjoy a double benefit: cheaper entry valuations plus a translation gain as foreign currencies appreciate. That’s a point in favour of the rest of the world.

Conversely, an investor who fully hedges their U.S. exposure via currency-hedged funds and ETFs may be more inclined to maintain higher U.S. exposure.

Investor Takeaways

How should an investor put these pieces together?

In short, the evidence suggests the probability of continued U.S. outperformance has fallen.

International markets trade at a discount of roughly a third to U.S. stocks and offer much higher dividend yields, while their earnings growth expectations are similar to the U.S.

Equally, the structural forces that have underpinned U.S. exceptionalism such as better productivity, deeper capital markets, a powerful technology ecosystem are still in place and may continue to justify some premium.

That all adds up to an outlook that remains bullish for U.S. stocks, but potentially more bullish elsewhere.

Beyond a Binary Choice

A binary choice between U.S. and international equities therefore misses the point. The rational response may be to treat U.S. equity funds and ETFs as longer term core holdings, but to lean more deliberately into global funds at this juncture.

That might mean increasing exposure to Europe and Japan, where earnings growth expectations are healthy, and to selected emerging markets that combine attractive valuations with improving governance and balance sheets.

It may also mean acknowledging that today’s global indices are unusually concentrated with American behemoths, and that a more balanced global allocation offers not just the prospect of better risk-adjusted returns but also a more robust portfolio if the next decade does indeed look different from the last.

Disclaimer: This article is prepared by Simon Turner. It is for educational purposes only. While all reasonable care has been taken by the author in the preparation of this information, the author and InvestmentMarkets (Aust) Pty. Ltd. as publisher take no responsibility for any actions taken based on information contained herein or for any errors or omissions within it. Interested parties should seek independent professional advice prior to acting on any information presented. Please note past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance.